WHAT IS BONACO?

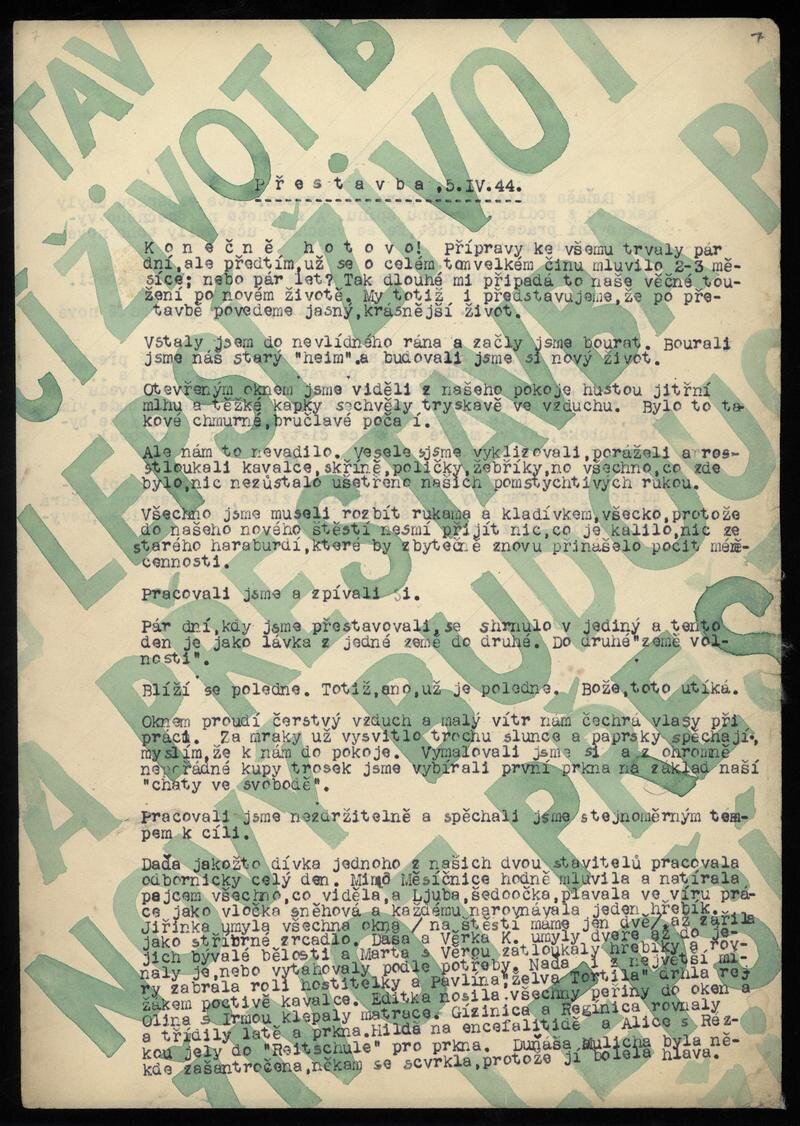

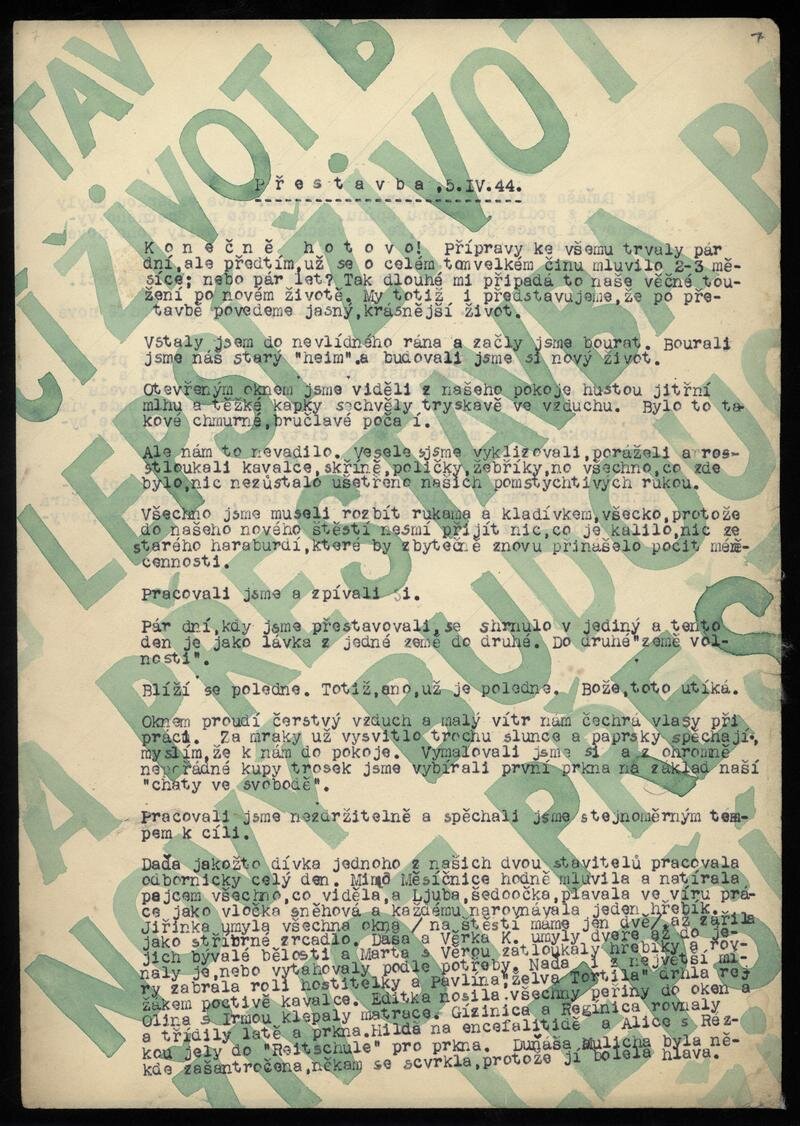

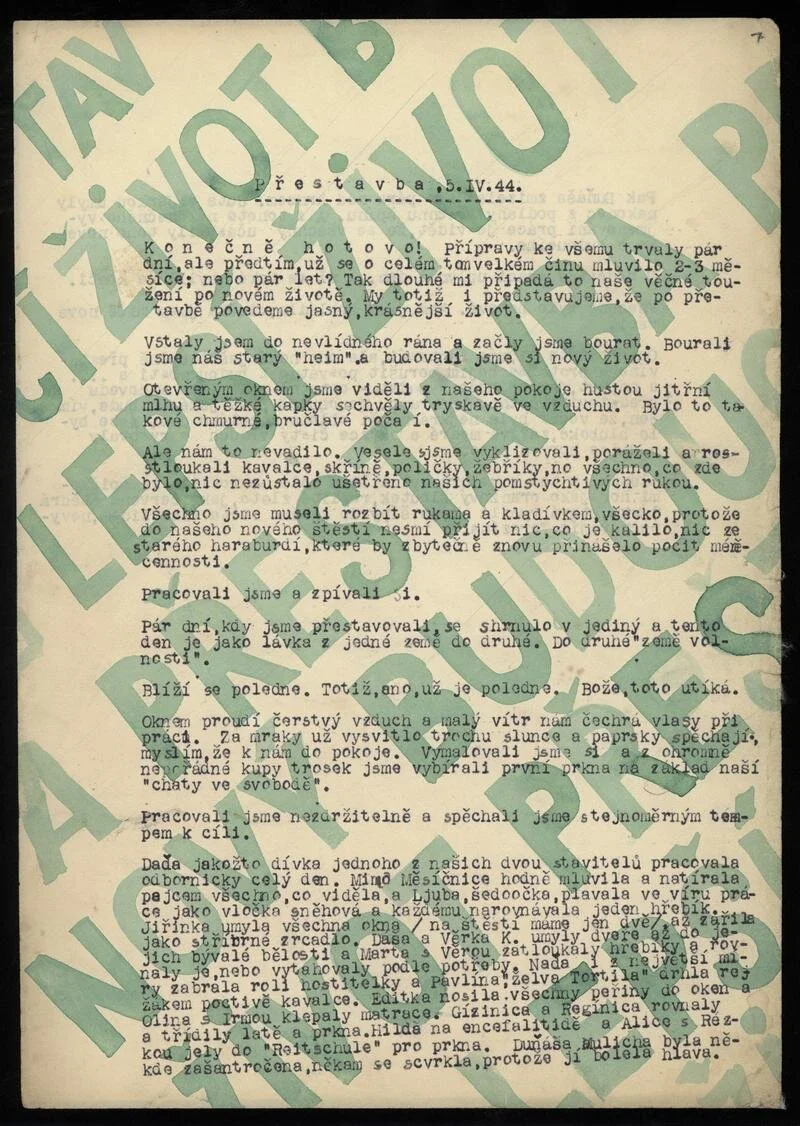

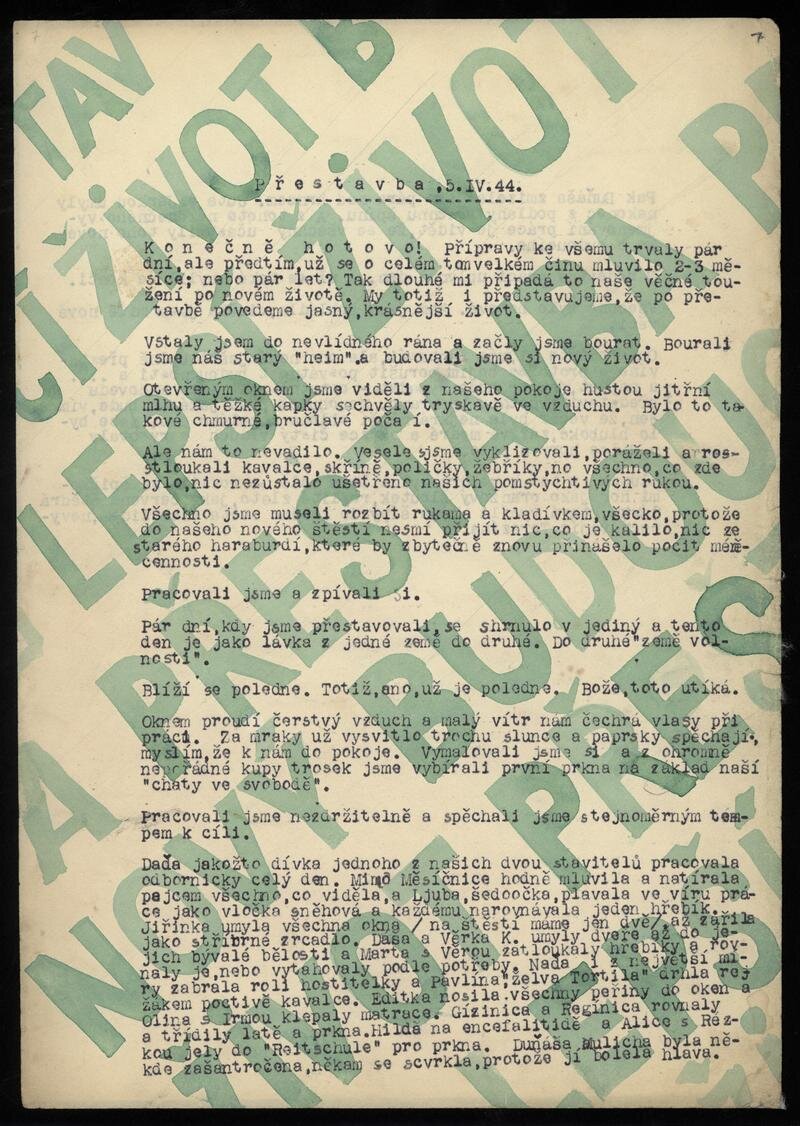

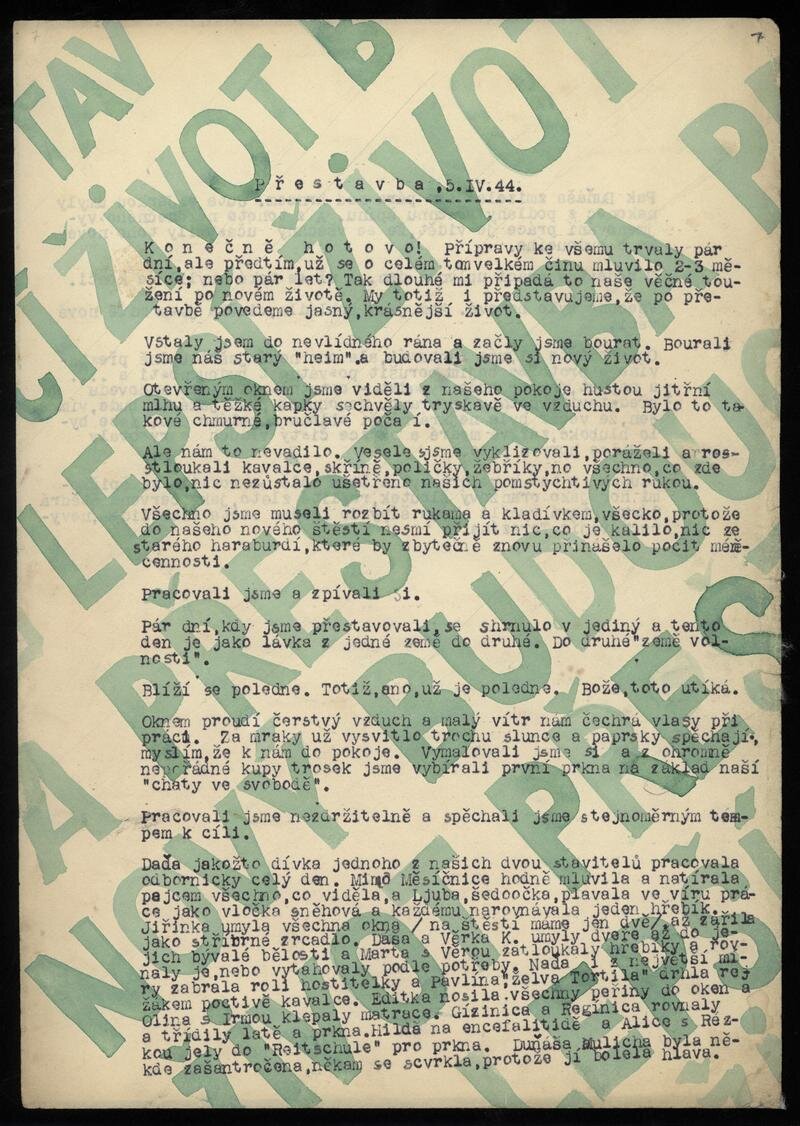

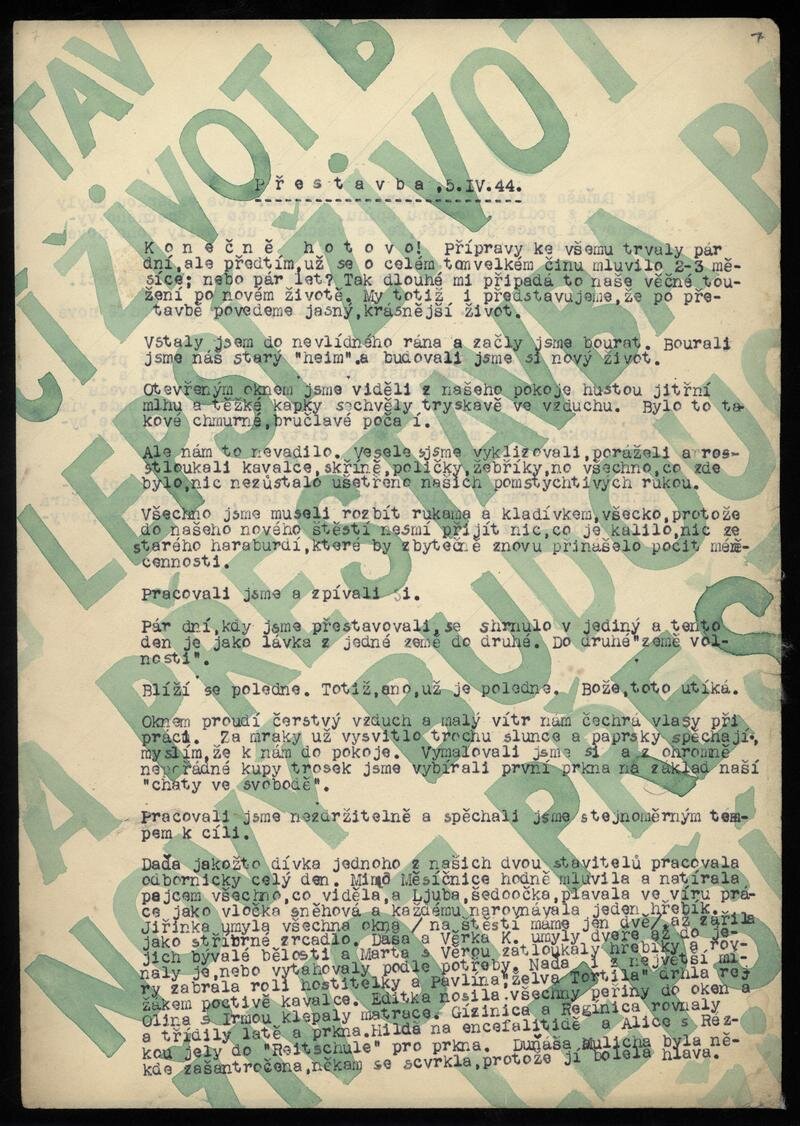

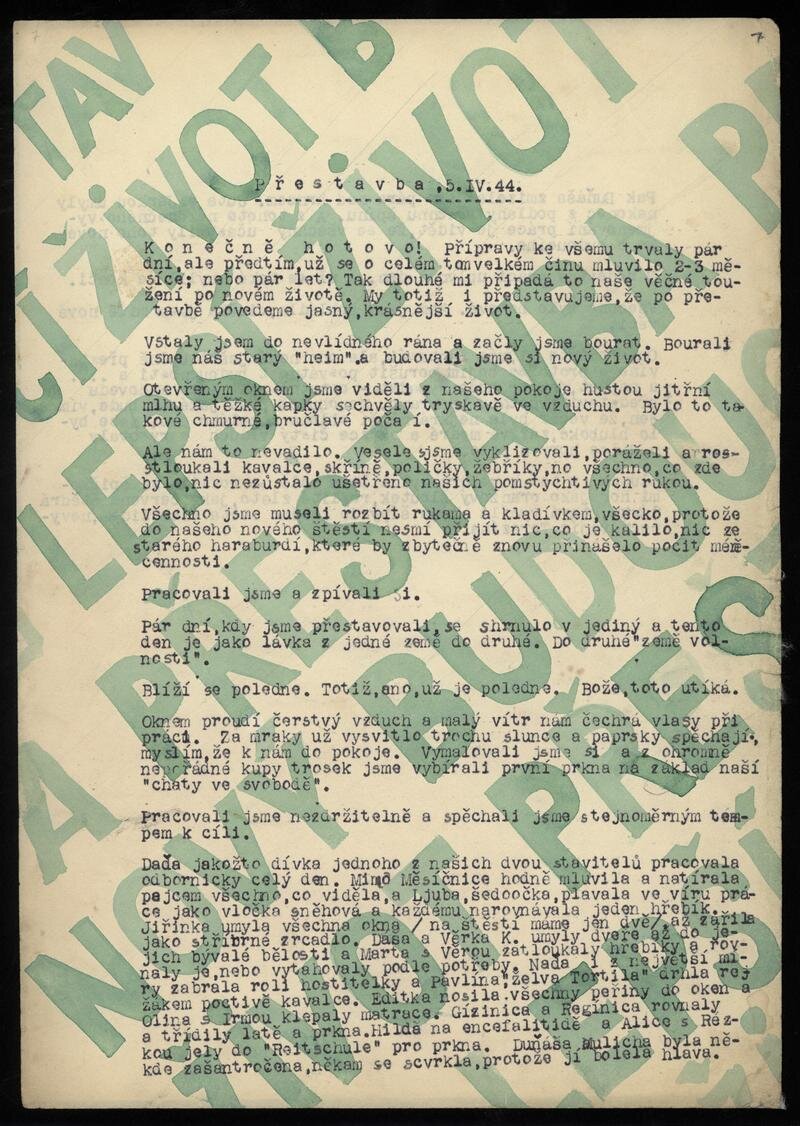

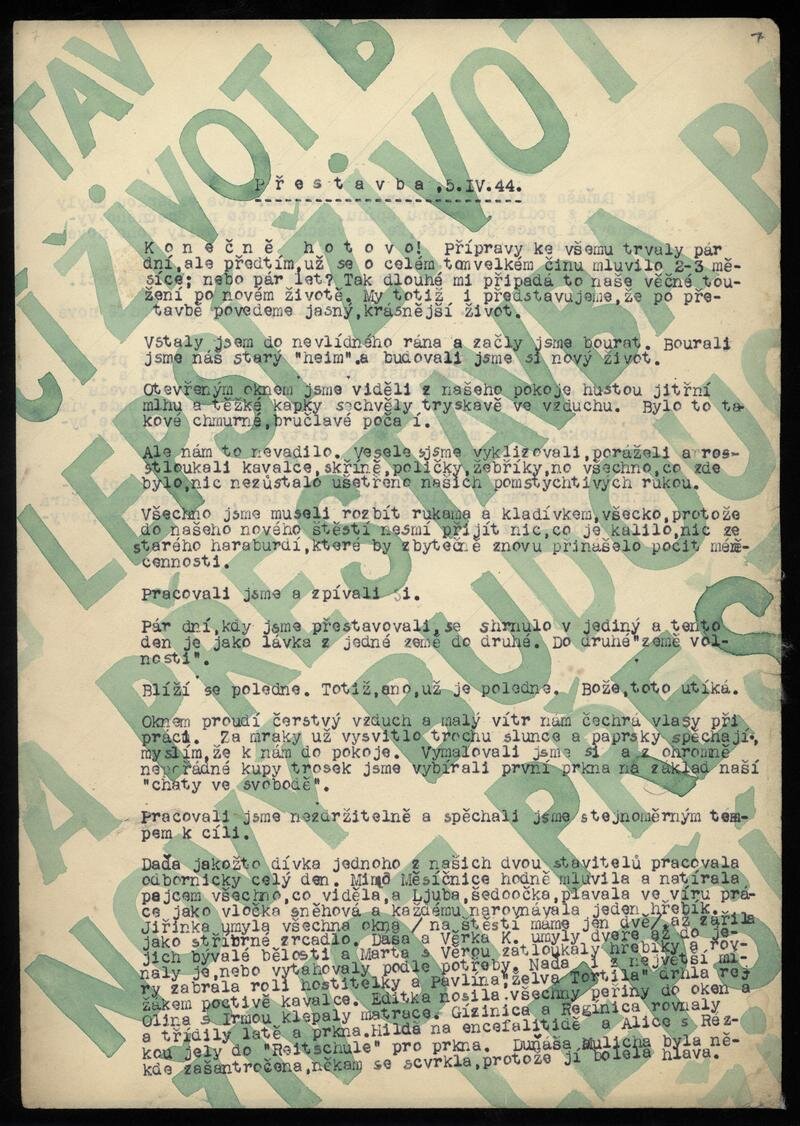

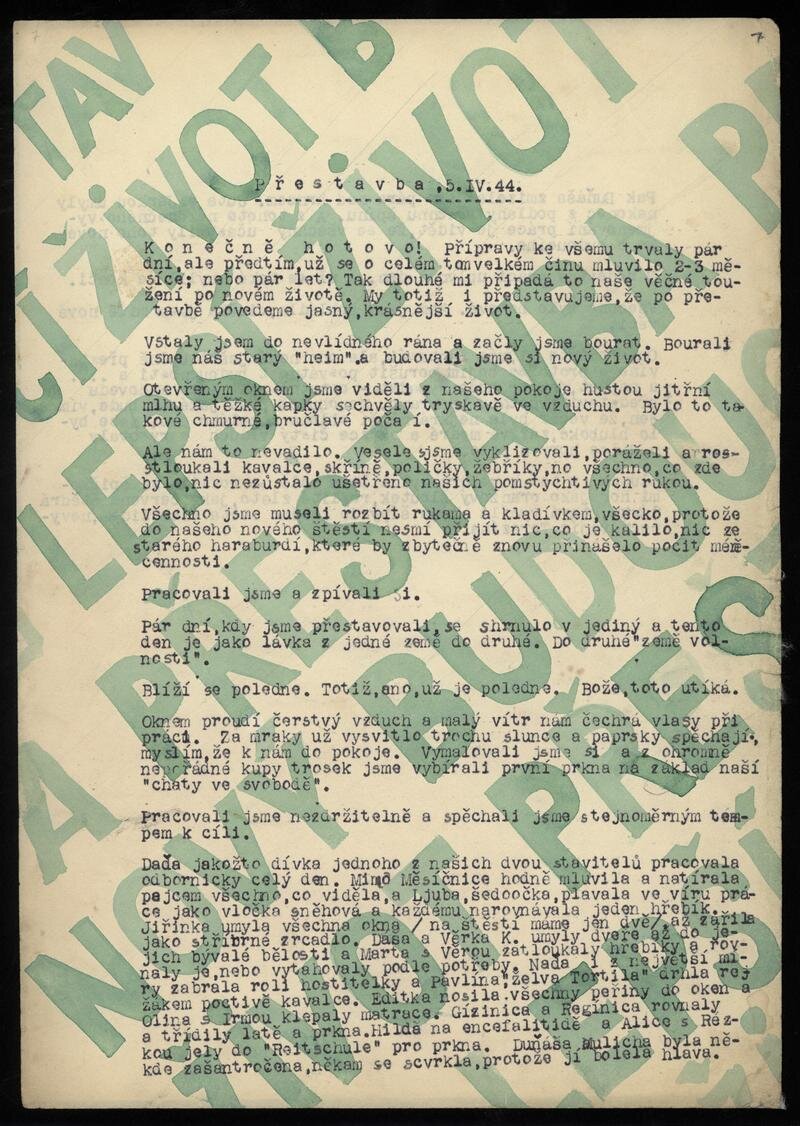

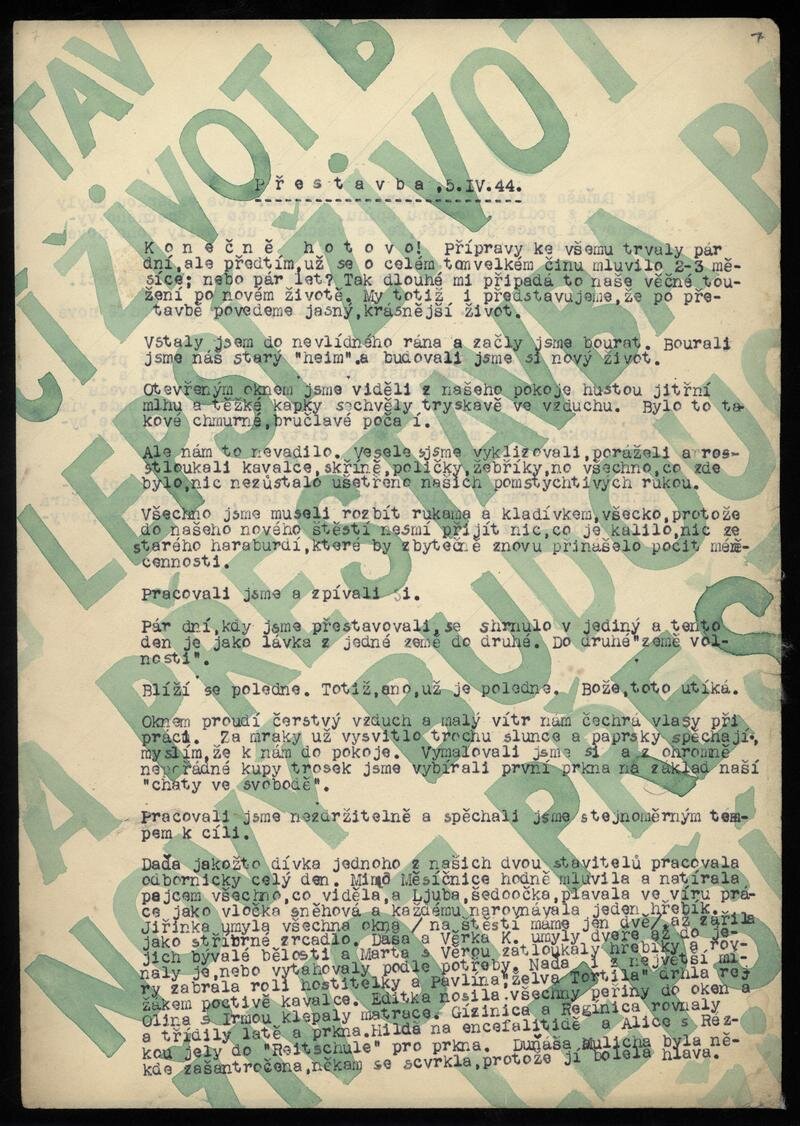

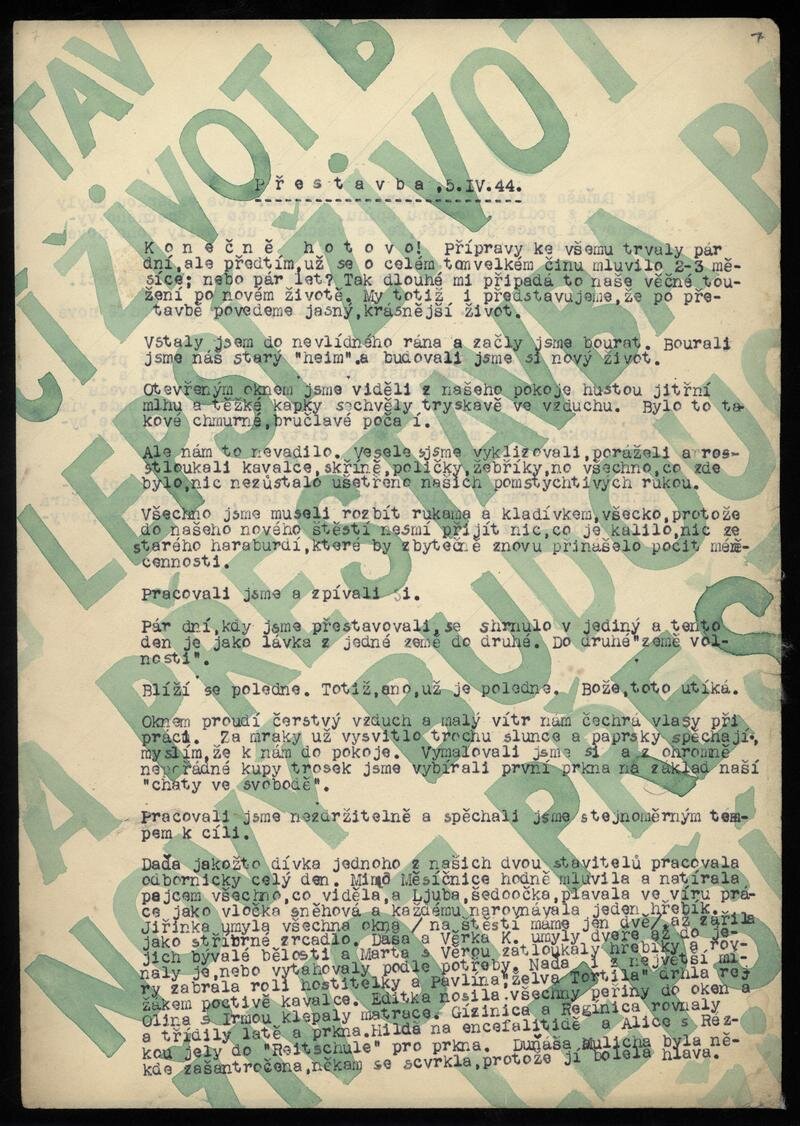

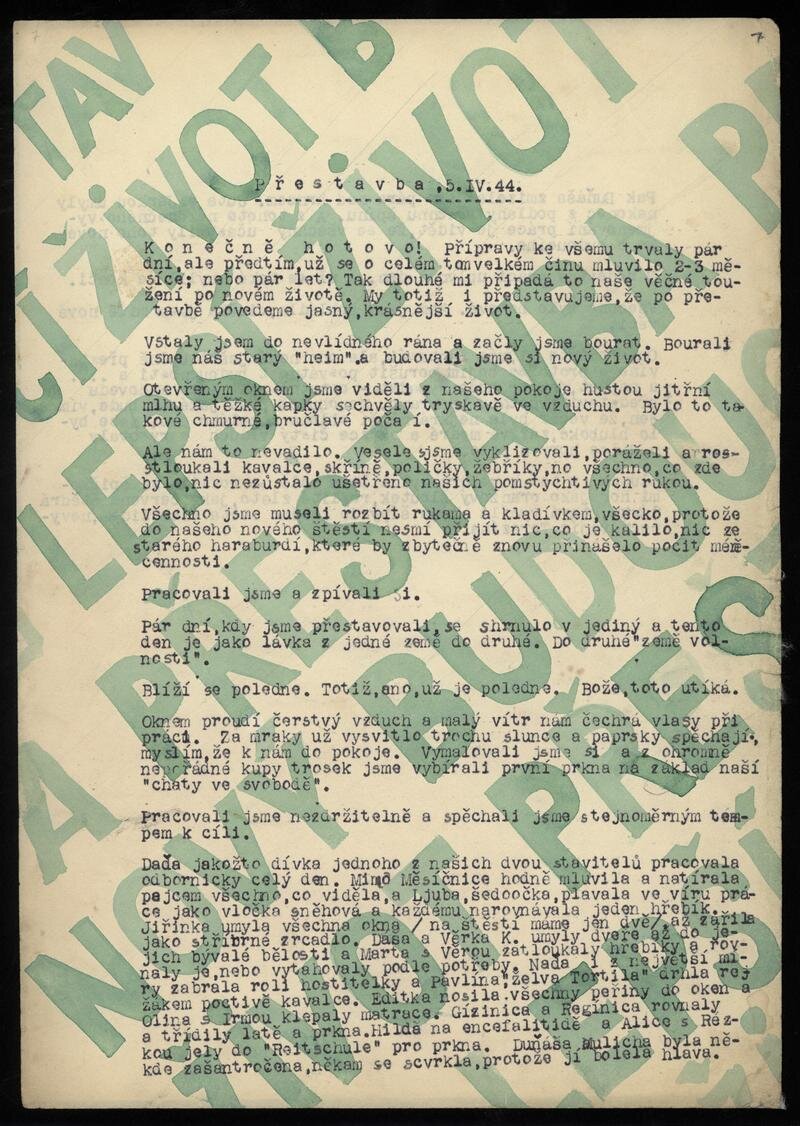

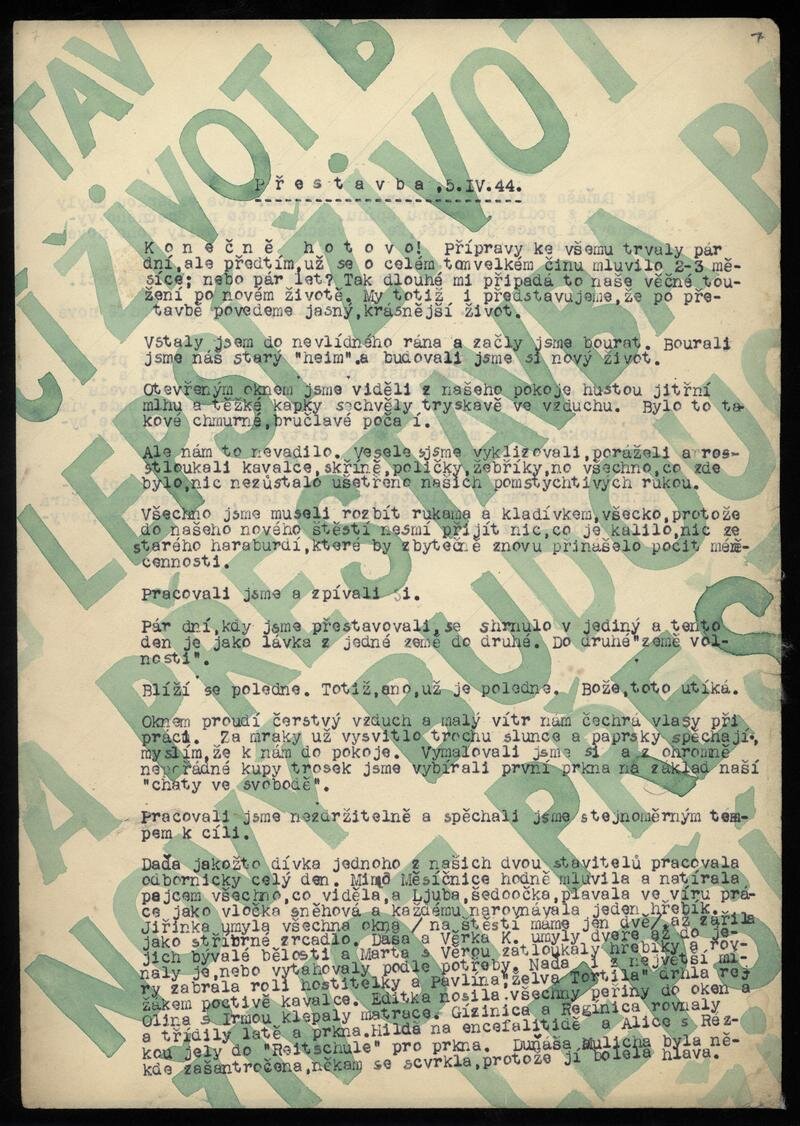

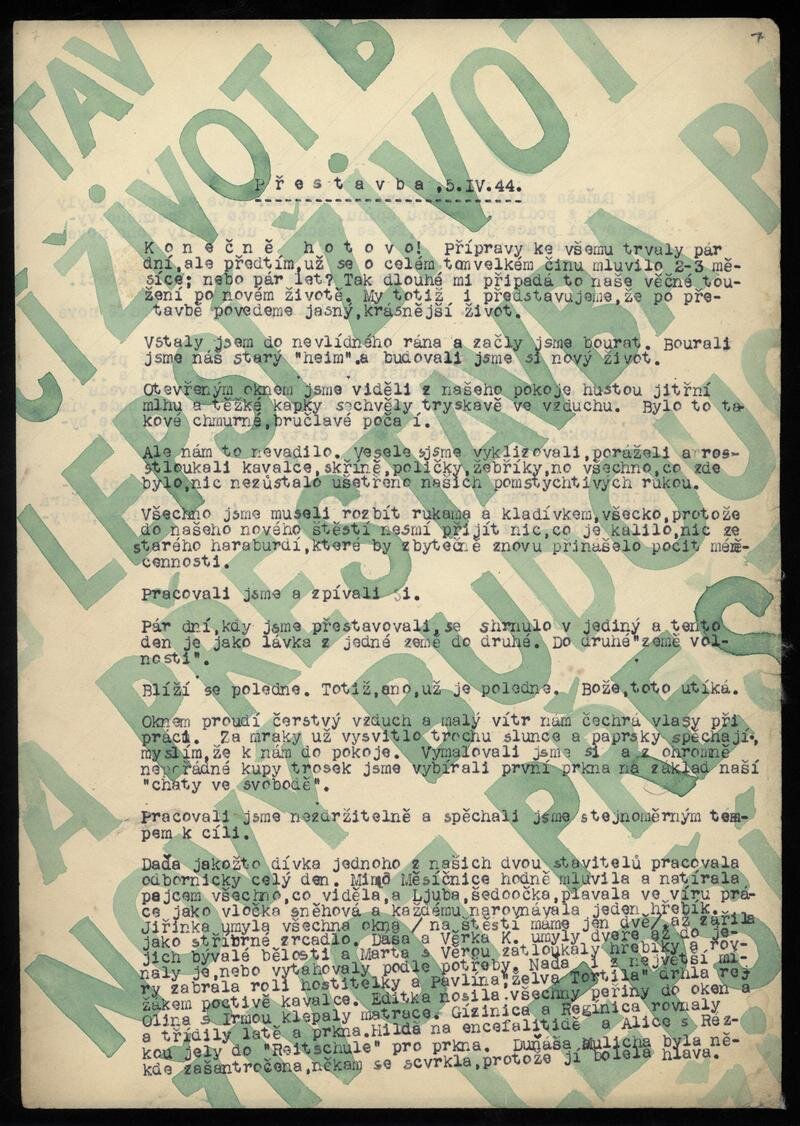

Bonaco is an underground handmade magazine – or zine – that was published from January 1944 to July 1944 by half-Jewish Czech girls aged 16-18 who were imprisoned in the Terezin Ghetto during World War II. Bonaco means “Mess on Wheels” in Czech.

WHY WAS BONACO CREATED?

Bonaco was unique among Terezin’s zines in that it was the only one created by young women. The magazine provided an outlet for teenage girls who’d lost virtually everything – homes, family, property, access to education – when they were taken to Terezin. Instead of school, these women prisoners were immediately put to work – in kitchens, in doctors’ offices, or in gardens.

“Our goal”

“It’s not just illusions,

It’s not empty talk.

We want to break through life,

We want to show strength,

Not physical but mental.

Life is a cruel fight,

And yet not so bad.

You just have to understand,

The most important thing to have is optimism.”

WHO WROTE FOR BONACO?

“The magazine is a job everyone could take part in. When every day involves danger or destruction, the magazine is a common interest that strengthens the spirit. We will not give up. We will continue, no matter what happens.”

About 30 girls contributed to Bonaco. Contributions were signed with initials or nicknames, making the determination of authorship difficult because some authors used multiple ways to sign their work. The following writers were the most frequent contributors to the zine:

-

Jarmila “JARKA” Steinerová

(b. 3/14/27, d. 1944 Auschwitz): Bonaco’s Editor in Chief grew up in Pardubice, which sits on the River Elbe and is about 60 miles east of Prague.

-

Dagmar “MAHULENA” Poláčková

(b. 2/17/26, liberated from Terezin): Bonaco’s writer was one of the few girls in Room #11 to not be sent to Auschwitz.

-

Miloslava “ MÍLA “ Böhmová

(b. 5/4/26, liberated from Terezin): Bonaco’s writer grew up in Nový Rychnov, a small town about 70 miles southeast of Prague. She worked in Terezin’s farms, Terezin’s kitchens and as a worker processing mica, a mineral used in stoves and kerosene heaters.

-

Erika “RIKA” Steinerová

(b. 12/13/27, liberated from Terezin) Bonaco’s writer grew up in Prague.

-

Lili “MERCI” Monathová

(b. 8/7/25, survived Auschwitz): Bonaco’s writer grew up in Brno and arrived in Terezin as an orphan.

-

Soňa “S.W.” Waldsteinová

(b. 11/28/26, liberated from Terezin): Bonaco’s illustrator, who was from Prague, contributed to the magazine primarily through her drawings, including those on magazine covers.

-

Hilda “HILDA” Úlehlová

(b. 8/18/25, liberated from Terezin): Bonaco’s writer grew up in Prague.

-

Judita “JULA” Lamplová

(b. 11/19/28, liberated from Terezin): Bonaco’s writer grew up in Prague.

WHERE WAS BONACO PUBLISHED?

“Although we are in Terezin, we aren’t losing our optimism or our zest for life and work.

Not only will our magazine reflect our cheerful and friendly life with its sometimes-gloomy moments, but it should be proof that we can do what we want.

Our horizon extends beyond the Ghetto, and that our interests aren’t limited by wooden barriers.

We want to convince ourselves that no one can beat us.”

Bonaco was produced in Room #11 of Terezin’s Building L414, where the girls lived. Any girl living in Room #11 could join the magazine which gave its creators the opportunity to explore how everyday life within the camp impacted their personal experiences. In order to improve their skills, the girls wrote papers and critiqued each others’ writings.

“There were 30 of us living in three-level bunk beds in one room. We decorated it in every way, with photos and pictures on shelves hung on the walls. And we kept order very carefully.”

Each room had an older counsellor to look after its child prisoners, and Room #11’s was Gertrude Sekaninová-Čakrtová, who was well-liked by the girls. Gertrude was vital to Bonaco’s creation by securing a typewriter and other materials that were needed to produce the magazine. And even though the girls had to work most of the day, Gertrude encouraged the girls’ efforts to publish the magazine in their spare time.

“Gertrude really took care of us from a cultural and mental point of view. She tried to teach us English, and introduced us to books and culture in general.”

Other activities included playing theater. For example, the girls read some of Shakespeare's plays, divided their roles, and performed the parts during the evenings. They also read books and studied foreign languages such as English, French and German. All of these activities led to closer friendships.

“All in common is a living desire to elevate from a mere dormitory to a real home of good friends."

Within the home, a food “fund” was also established for girls who were either sick or did not receive food packages from non-Jewish relatives at home, as Terezin’s prisoners were scarcely fed. The girls who received the packages handed some of them over to the fund, which was then divided among the less fortunate. In this case, the magazine played the role in some of the girls’ well-being by recording the fund’s activities and publicizing the fund as an expression of friendship and solidarity.

“We know very well that everyone offers to help out their friends, but there is something more about the fund. We learn to think ahead to make sure everyone’s taken care of. And we recognize that the growth of small contributions into one big one reflects the small power of all common actions.”

WHAT DID BONACO’S CREATORS WRITE ABOUT?

“A key article should be published if it tells us clearly and distinctly the slightest thing concerning the writer or her friends, home or ghetto, Terezín or the whole world.

However, the attempt at fiction must be judged according to a stricter scale, primarily in the interest of the author, but also in favor of the readers.

The writer must have the right degree of self-criticism and courage. Self-criticism is not to be a censor who whitewashes his work and throws it in the trash, but a mentor who, together with courage, is a good beginner's guide. The things that will be printed on these pages must both educate and respect the tastes of readers.”

“Here, we want to find behind the expressed idea of experience, design, plan, criticism – how a young girl, no matter whose name, lives in Terezín in 1944.”

Bonaco differed from other Terezín magazines mainly because the content reflected young women's interests. They touched on topics that are still relevant today while drawing attention to the problems that resonated in society at the time - the lower salary of women compared to men; the work performance of women compared to men; or the dependence of women on men. The girls also discussed topics ranging from of motherhood and child- rearing to the suitability or unsuitability of institutional care to the time-consuming nature of education. Some writers penned articles supporting emancipation.

“We are in favor of a thorough women's education and training, or gainful activity. Above all, there is an effort to achieve full equality. Only a woman completely equal to a man can find the right friend for life.”

The girls tried to educate themselves at all costs. For this purpose, they invited fellow prisoners who were experts on various topics to lecture them in various fields and share their experiences with the young women. Among the lecture topics covered by the magazine were memories of high school years, the French Revolution, Modern Art, and Chinese poetry.

“Write a lot in both parts of the magazine. That is: think a lot, live in depth, and dress your thoughts, ideas, images of a dress, shining with all colors of fantasy and novelty, but perfectly cut with thought and perfectly-sewn honestly.”

Bonaco also included a recurring column called “The Daily News,” in which the Terezin opening of a central library in the Ghetto – all of the books were donated by prisoners – was publicized and celebrated as a boon to Terezin’s growing group of magazine writers, editors and illustrators.

““It is a small, tastefully decorated library where everyone really works with love. Every day, there are a lot of children who will become passionate readers and use books to forget about unnecessary worries. Several librarians are employed here, and they're very willing to accept books to add to the library's treasures and to issue identification cards to new members.”

Armed with their self-sought education, Bonaco’s writers challenged each other within the magazine’s pages. In addition to publishing fiction, poetry and biographies of renowned Czech writers, Bonaco included a short-story competition based on the concept of “Footprints in the Snow” as well as a fairy-tale competition based on artwork the writers were provided. One article titled “My Future” stemmed from a request within the magazine’s pages for the girls to consider ideas on how to end the war. Bonaco had a recurring section called “Veselý koutek“ (“Cheerful Corner”), where the author wrote facts about the Ghetto in an order in which each successive sentence begins with the next letter of the alphabet.

“Who knows? Maybe the magazine won't last and we'll get tired of it after a while.

Maybe it will disappear after a few issues because we’ll have more important things to worry about.

But let us also be hopeful, that even if it’s harder than we thought at the beginning, we will overcome those difficulties.

That nothing will discourage us.

And that one day, we’ll leaf through our mementos and proudly show them to our friends.”