WHAT IS DOMOV?

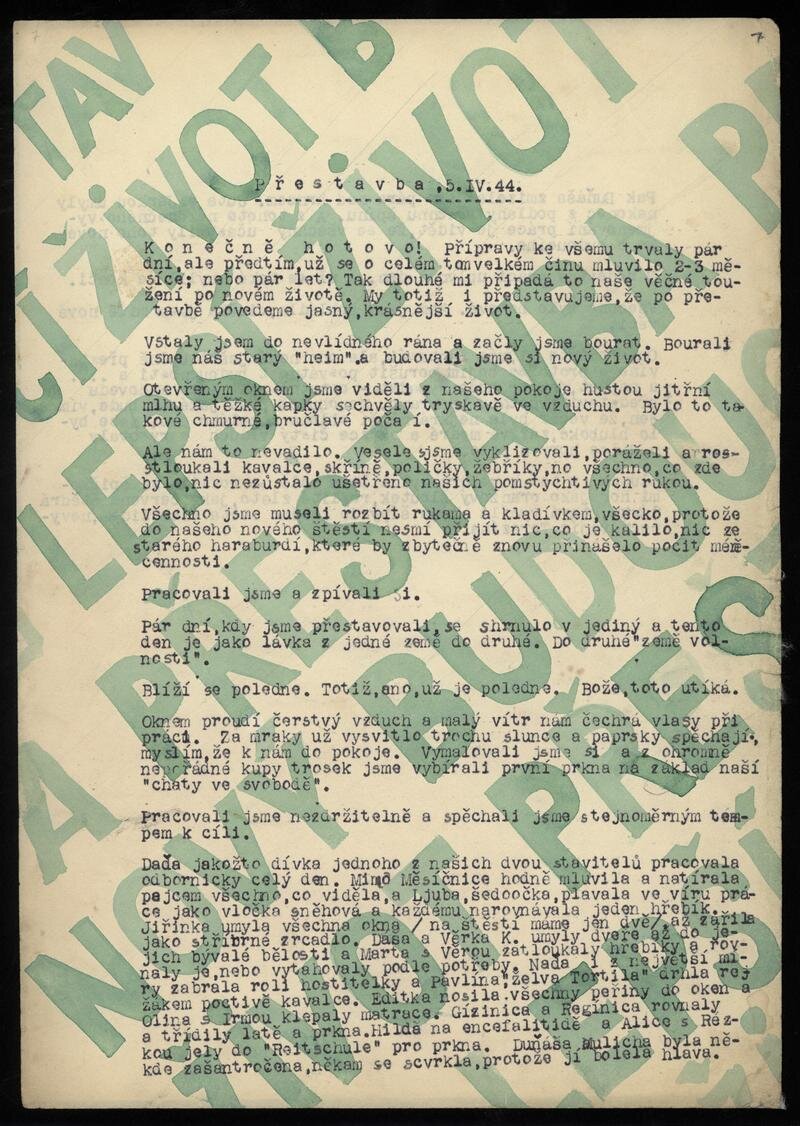

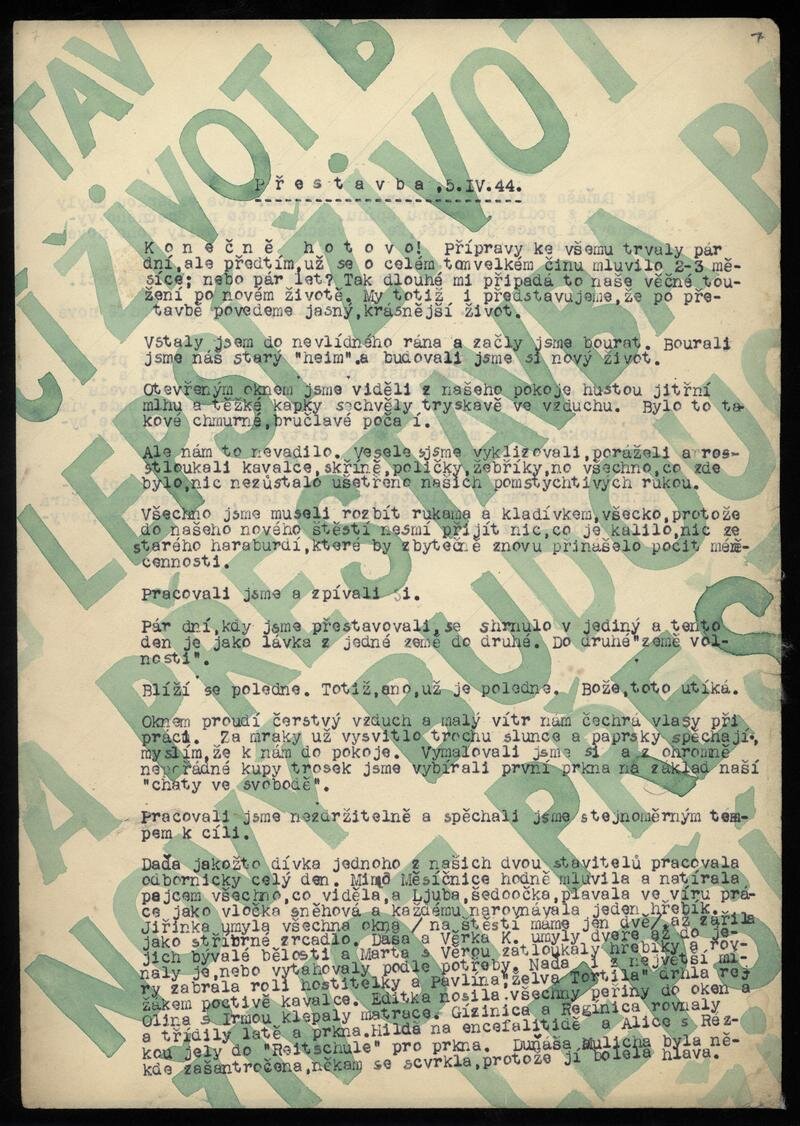

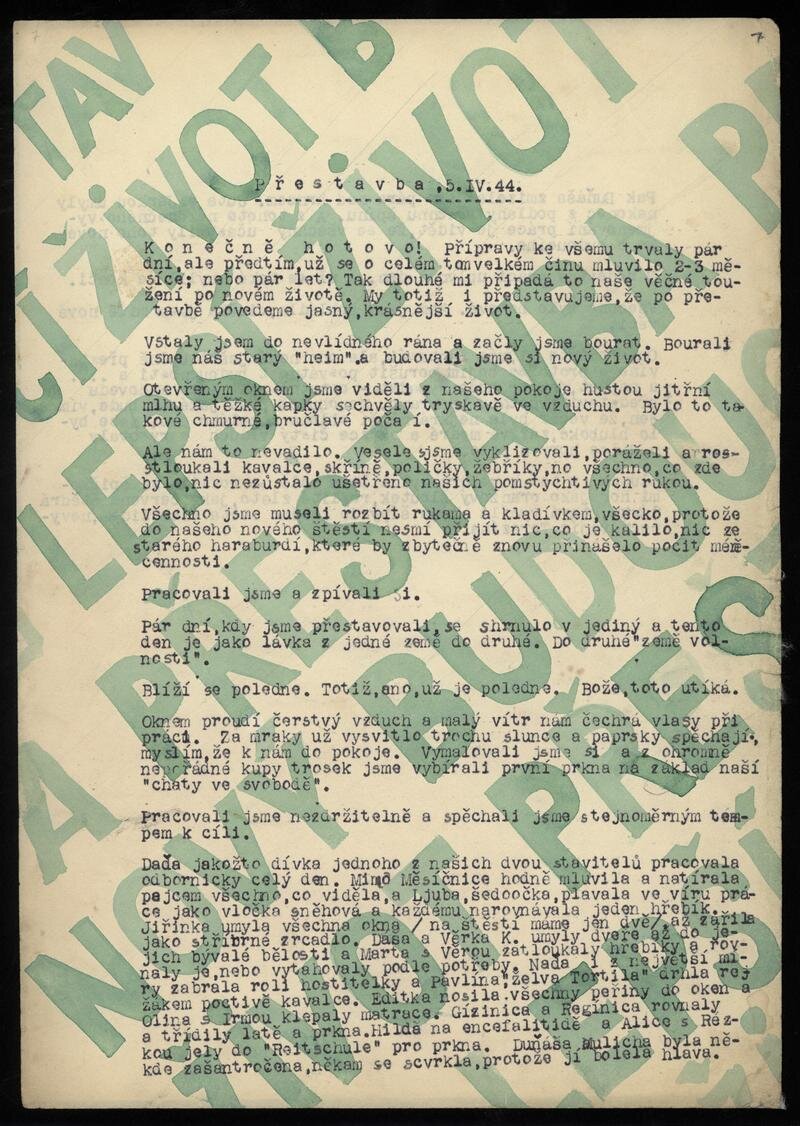

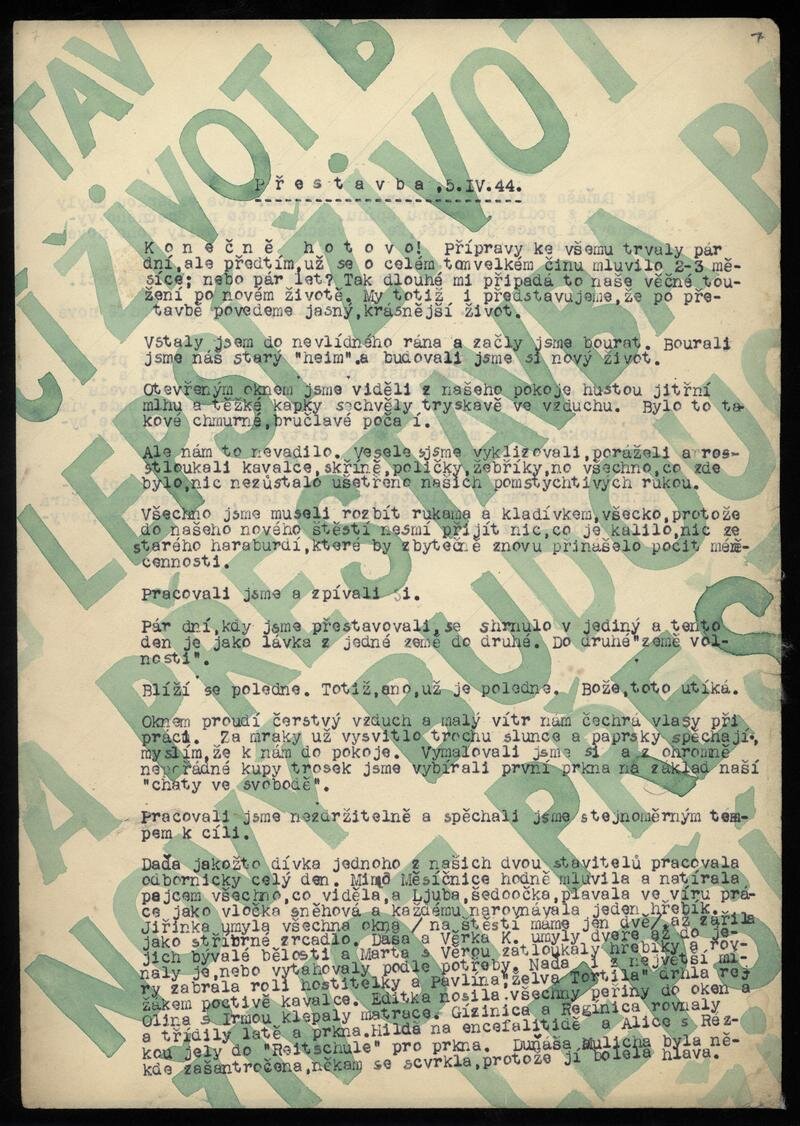

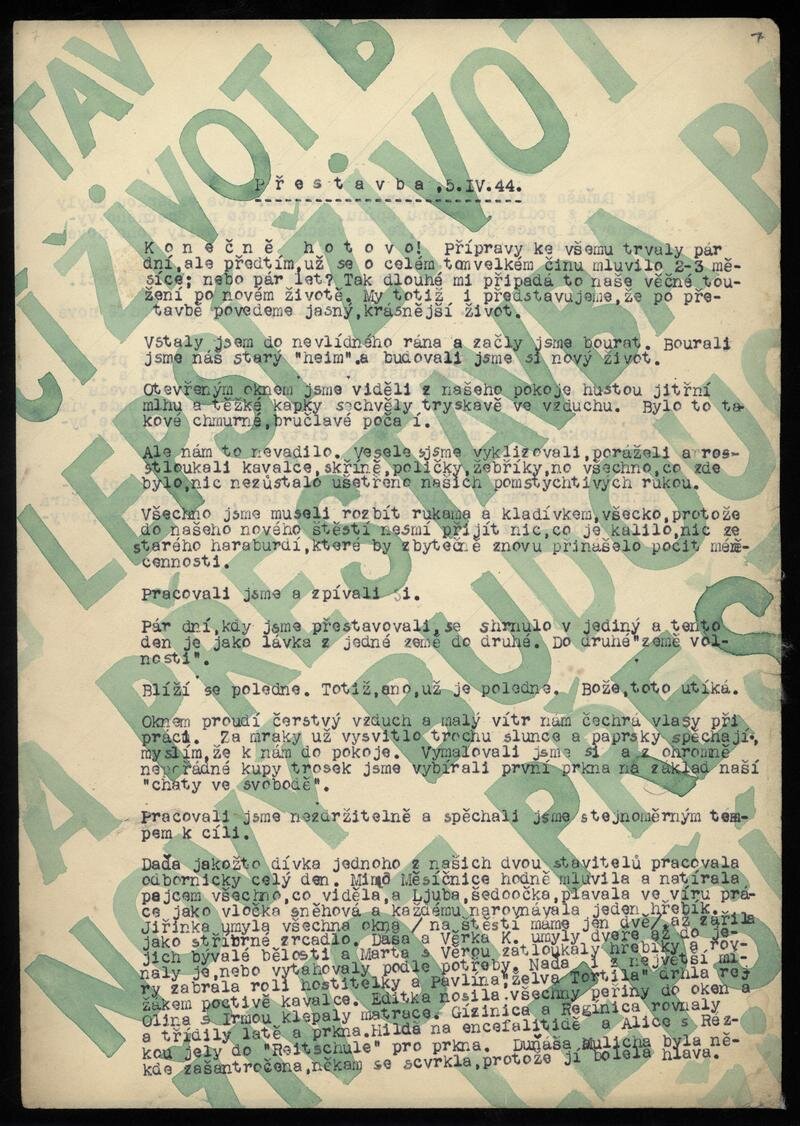

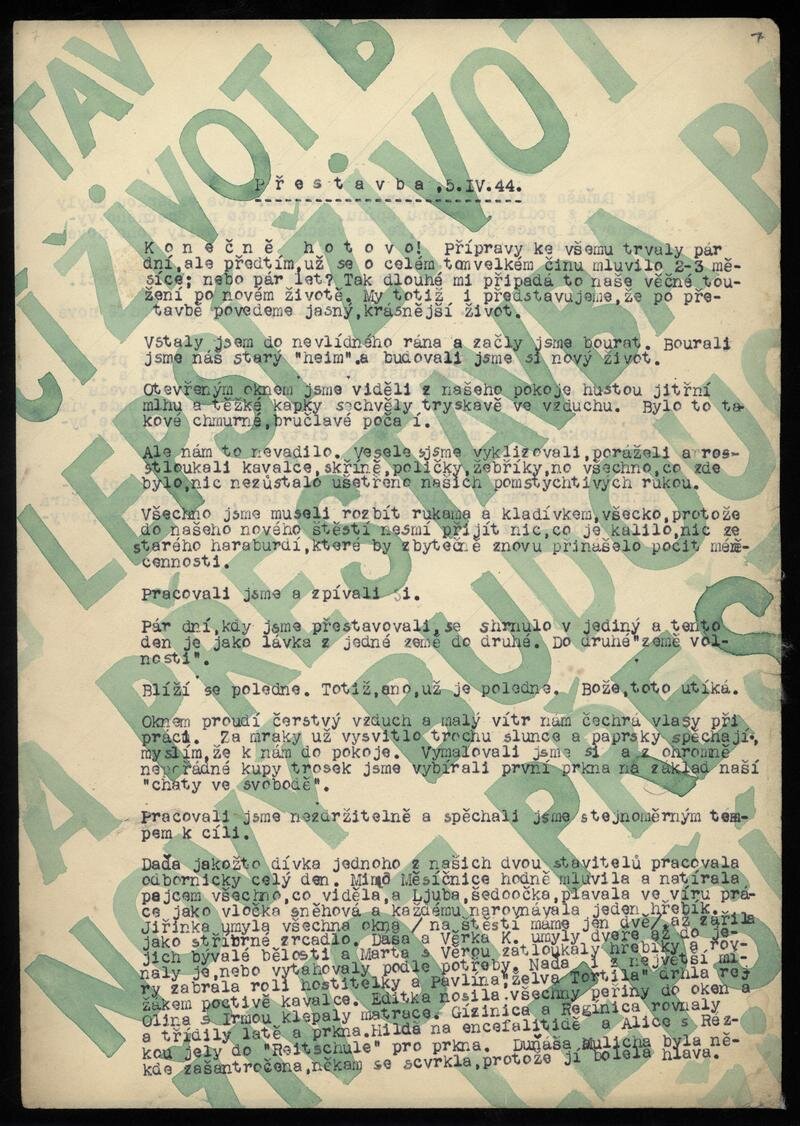

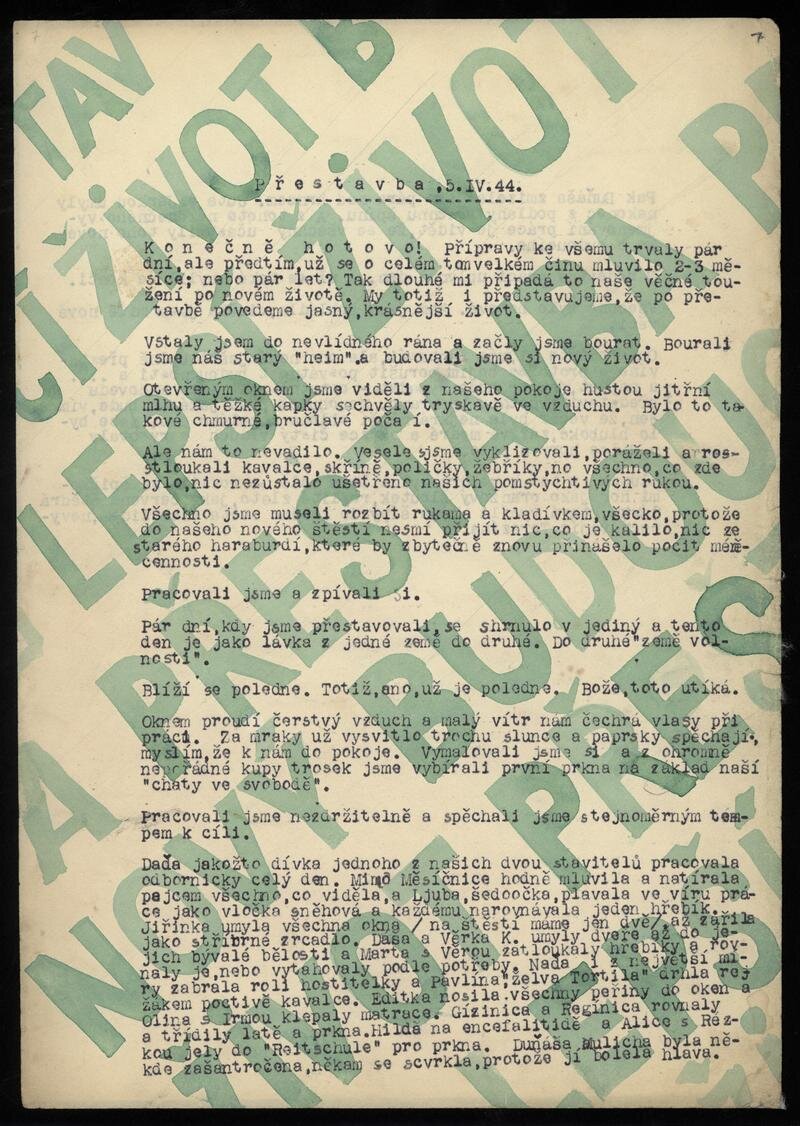

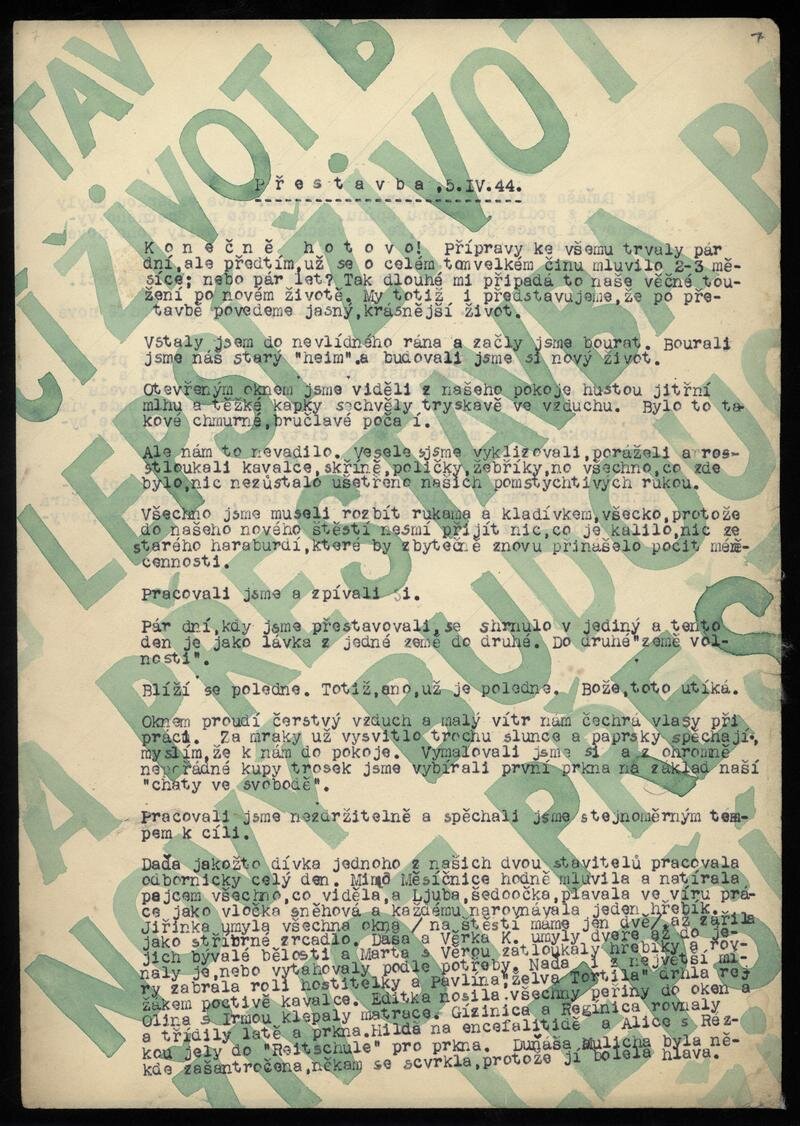

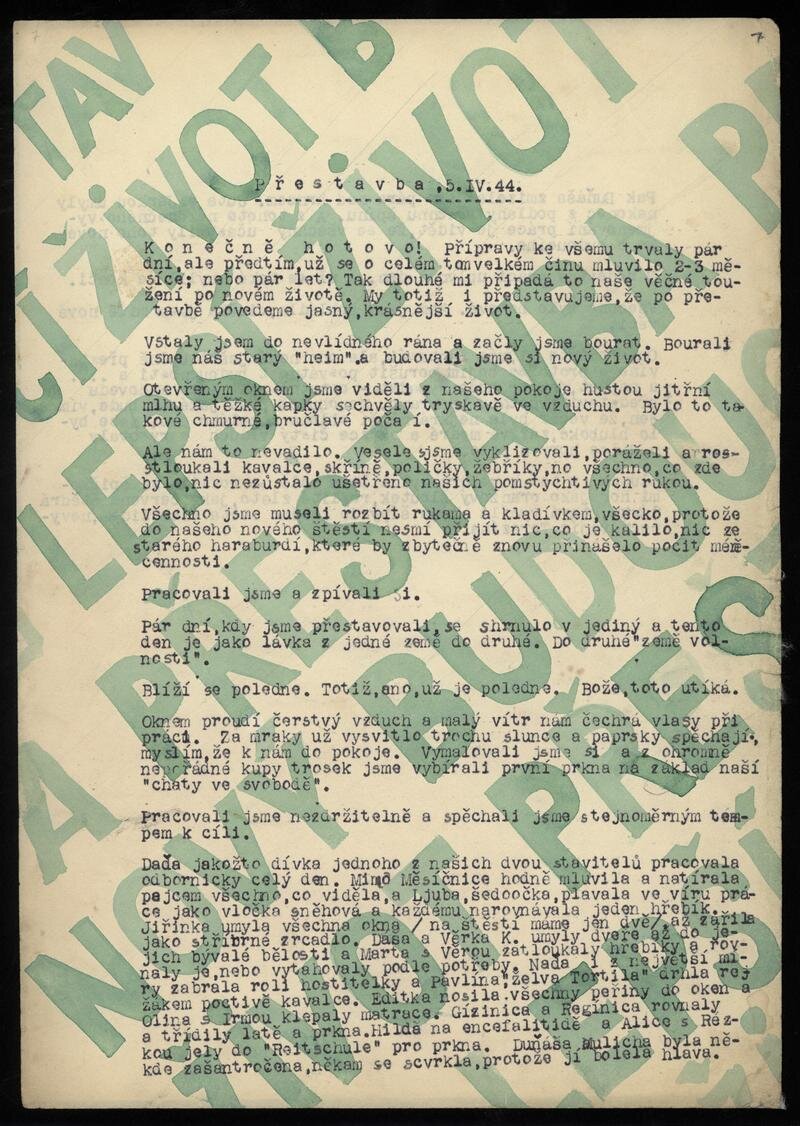

Domov is an underground handmade magazine – or zine – that was published from December 1943 and May 1944 by two 12-year-old boys who were imprisoned in the Terezin Ghetto during World War II. Domov means “Home” in Czech.

WHY WAS domov CREATED?

“Dear Readers! We are starting to publish a magazine for the Hanukkah holiday and for a change in your monotonous life. If you like it, we will be happy to continue publishing more issues.”

Domov was created by Martin Glas and Petr Seidemann, two close friends as a way to keep their minds, and their friends’ minds, off the trauma of imprisonment and potential deportation to death camps. In this case, the December 1943 transports of many of their bunkmates as well as their room counsellor Hanka Sachslová spurred Martin Glas and Petr Seidemann to create a magazine to keep them busy and lift their spirits.

“In order to come up with other ideas and also entertain those friends who stayed and could read, my friend Petr Seidemann and I began to publish the magazine DOMOV,” wrote Glas.

WHO WROTE FOR DOMOV?

“We imagined that we would reach real readers, even though they were mostly younger than us.”

Martin Glas and Petr Seidemann became close friends (they were born only five days apart) while imprisoned along with 40 other boys in the Hamburg Barracks.

-

Martin “MACEK” Glas

(b. 6/16/31, liberated from Terezin): Domov’s Co-Editor-in-Chief grew up in Prague. "I vaguely remember sitting once at home at dinner in April 1942, when the doorbell rang and brought us a summons for transport to Terezín…In the Magdeburg barracks, I – a still-spoiled 11-year-old boy – felt the first impact of the harsh Terezín reality, which fortunately eventually had a positive effect on me.”

-

Petr Seidemann

(b. 6/21/31, liberated from Terezin): Domov’s Co-Editor-in-Chief also grew up in Prague. “Our magazine is proof that the absolute loss of freedom and contact with the family, illness, insecurity and – why not admit it, the great fear for life and the future – did not prevent us from trying to live in a concentration camp normally, as our mental defense.”

WHERE WAS DOMOV PUBLISHED?

“One day a caretaker came to me and asked me if I would give up my mattress, because I was big for my age and other children came without mattresses. So I gave up my mattress, and slept on a blanket on the ground.”

– Martin Glas, Co-Editor

Domov was published every two weeks first at the boys’ Room #236 in the Hamburg Barracks. Martin Glas said that in the beginning their home didn’t have beds. Everyone had to sleep on the floor on mattresses. Meanwhile, fleas and bedbugs were a constant nuisance. Later, bunk beds with ladders were added to the home. And there was a large table where the editors wrote and drew.

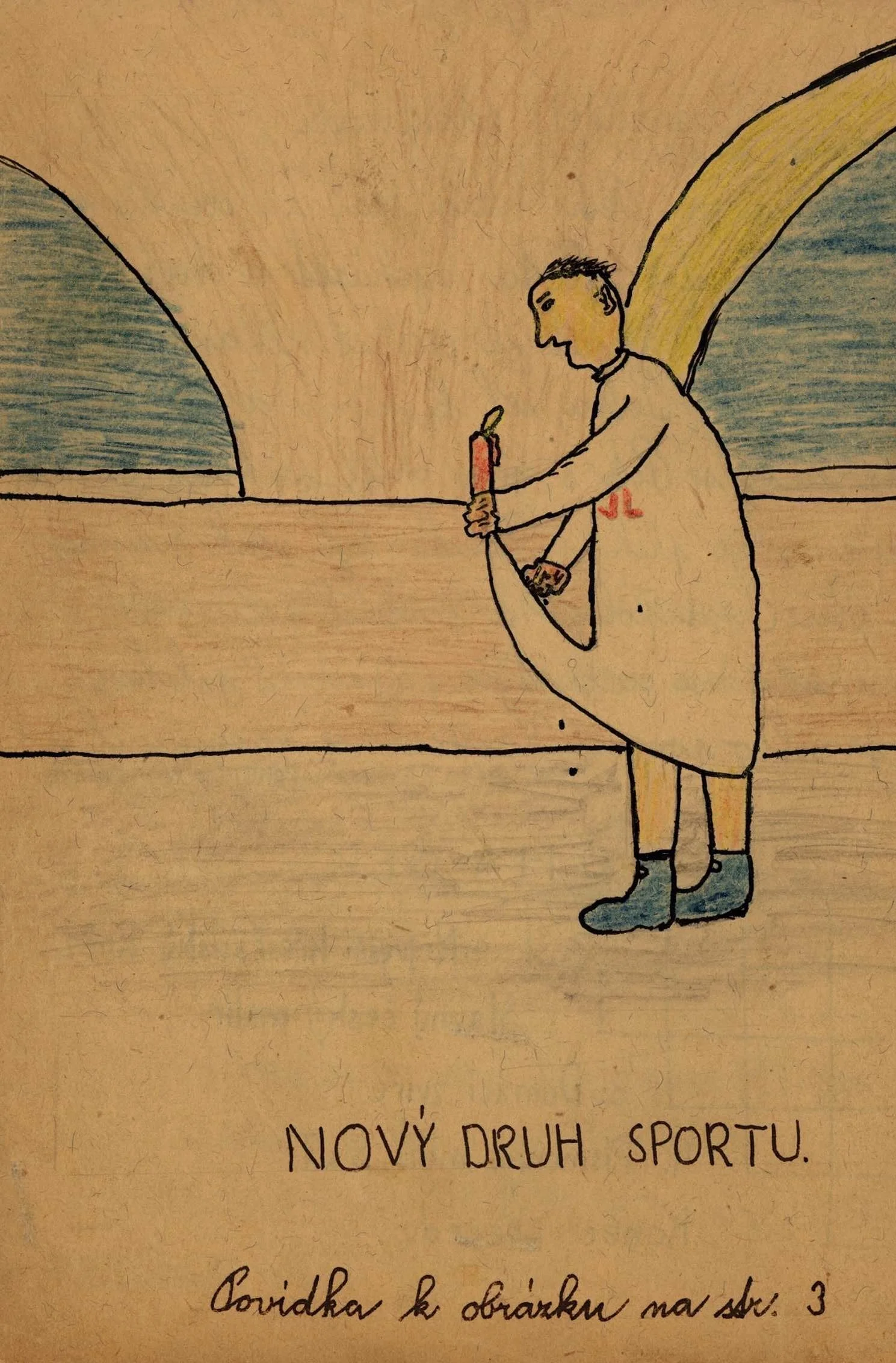

“A New Kind of Sport”

"We sent a reliable agent to the scene, who found out this: Every day at one o'clock in the morning, Jiří Lágus gets up from his bed and scares himself into the corridor with a candle in his hand. As we were told, he killed two fleas last night, seriously injured three, and one jumped by the neck. Tired from this hard work, he went to bed again. The result of this useful sport was unique. The next day, only 28 fleas were found on Jiří Lágus!”

In January 1944, the boys were moved from Room #236 to Room #2 in Building L417, a former school that was converted into a home for Czech boy prisoners. Here, the boys were overseen by educator Rudolf Weil. Still, it wasn’t easy to publish Domov. Because the other boys were younger – mostly between nine and 12 years old – many could barely read and most were more interested in sports than writing for a magazine.

“Don't just read, but WRITE !

What do you do in your free time?

WRITE for a magazine!!!

The magazine is written for you.

That's why you write for it!”

Still, the editors tried to get the boys to write by announcing a short-story competition and promising that the winner’s work would be published in the magazine, but the editors had to postpone the deadline due to lack of entries. In another attempt, the editors announced that one page in Domov would be fully reserved for news from readers, but the editors didn’t receive enough messages to fill the reserved space, so over time, this initiative disappeared.

“The name of the informant of the best news will be published and eventually the informant will be rewarded.”

Regardless, Martin and Petr had the benefit of publishing Domov without interference from any adults, and focused much of their efforts on topics that were entertaining, instructional and educational rather than anything critical. Recurring columns with titles such as “Here You Will Find…”, “Did You Know?” and “Have You Heard?” included knowledge tests on subjects such as broad as geography, history and sports, and as specific as Braille or Russian tea. The editors also experimented with the magazine’s structure by periodically adding crossword puzzles, jokes, pranks, optical illusions, riddles and advertisements.

“If you want to read our magazine, you must never eat while doing this! You must also have clean hands if you want to read DOMOV!”

WHAT DID DOMOV’S CREATORS WRITE ABOUT?

“Become a reporter! We need news! We need your help! Take note of all the little things and write them to us!

“I flew a plane that started burning, and I fell to the island. I can't write anymore because I'm dead.” -unknown writer, Domov

As part of the editors’ efforts to entertain Domov’s readers, some of the magazine’s content served to provide an escape of sorts, like the novel titled “Twelve Years of Detectives,” which was published in excerpts throughout the magazine’s existence.

But much of the content was inspired by life in the Ghetto. One early article describes 1943’s Hannukah celebration within Terezin. Another was a recurring feature called “Old Terezin,” which included cut-out cards with the history of the town as well as advertisements from a pre-war ticket guide to Terezín and the surrounding area that the editors found.

Domov also included special editions marking extraordinary occasions. One was about a falconry ceremony that included a string orchestra, a choir and Hebrew songs as well as readings of early 20th century Czech poet Jiří Wolker.

“And finally, dear readers, we can tell you that, during the performance, we forgot that we are in Terezín,” the issue concluded.