WHAT IS KAMARAD?

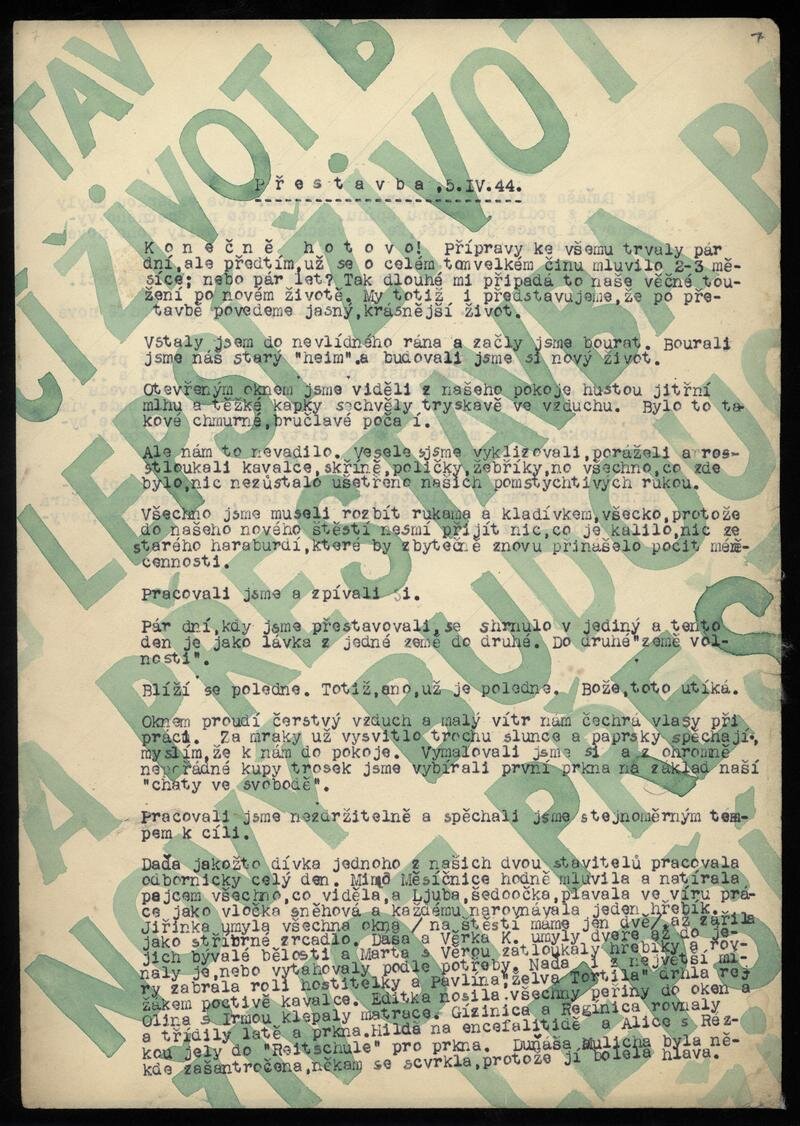

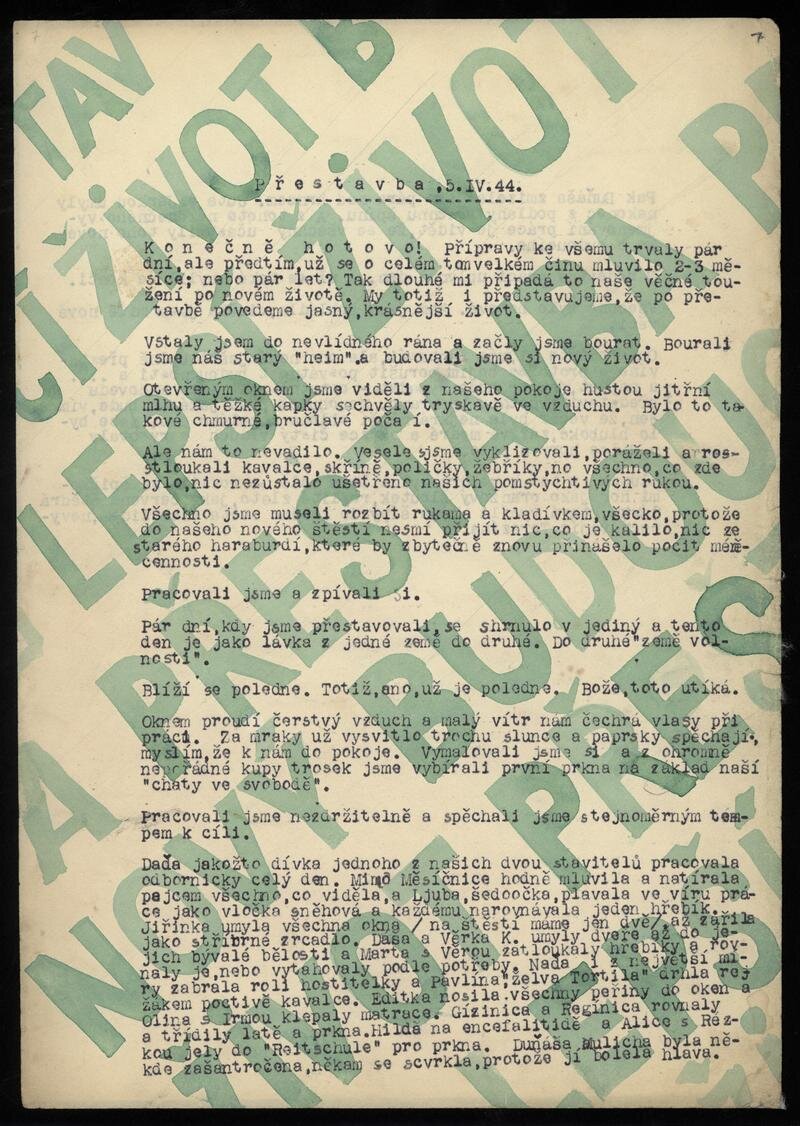

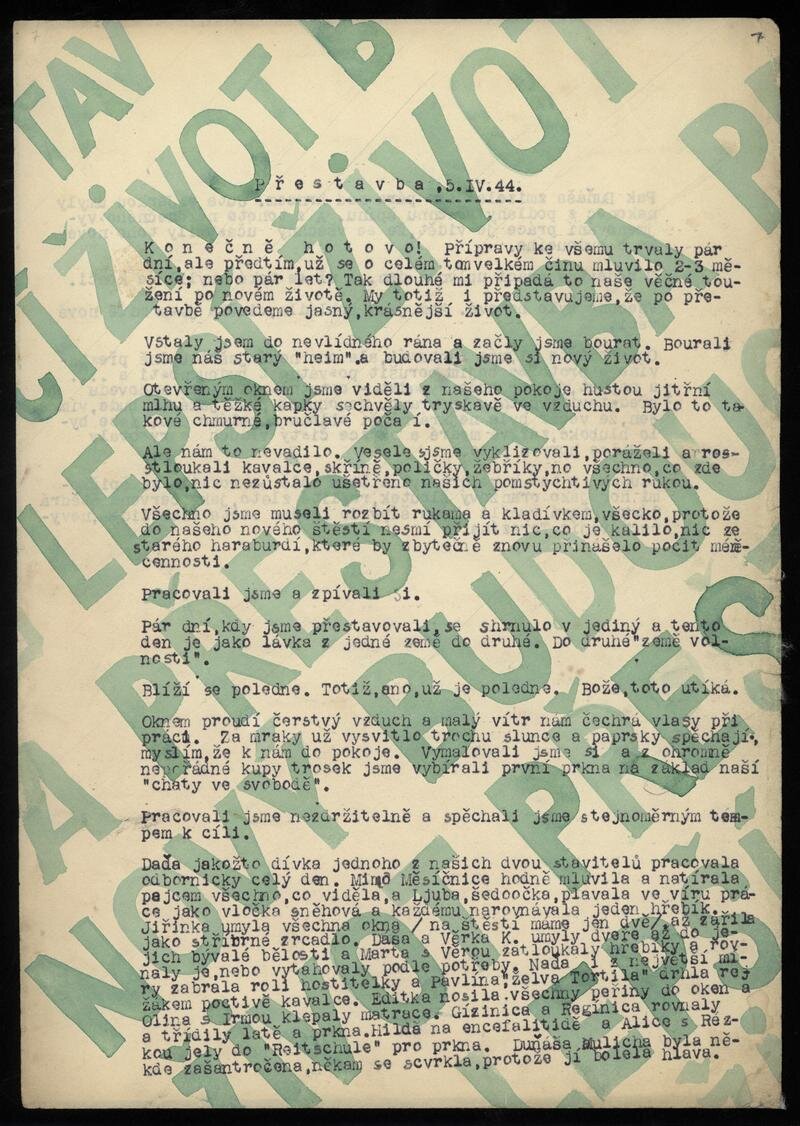

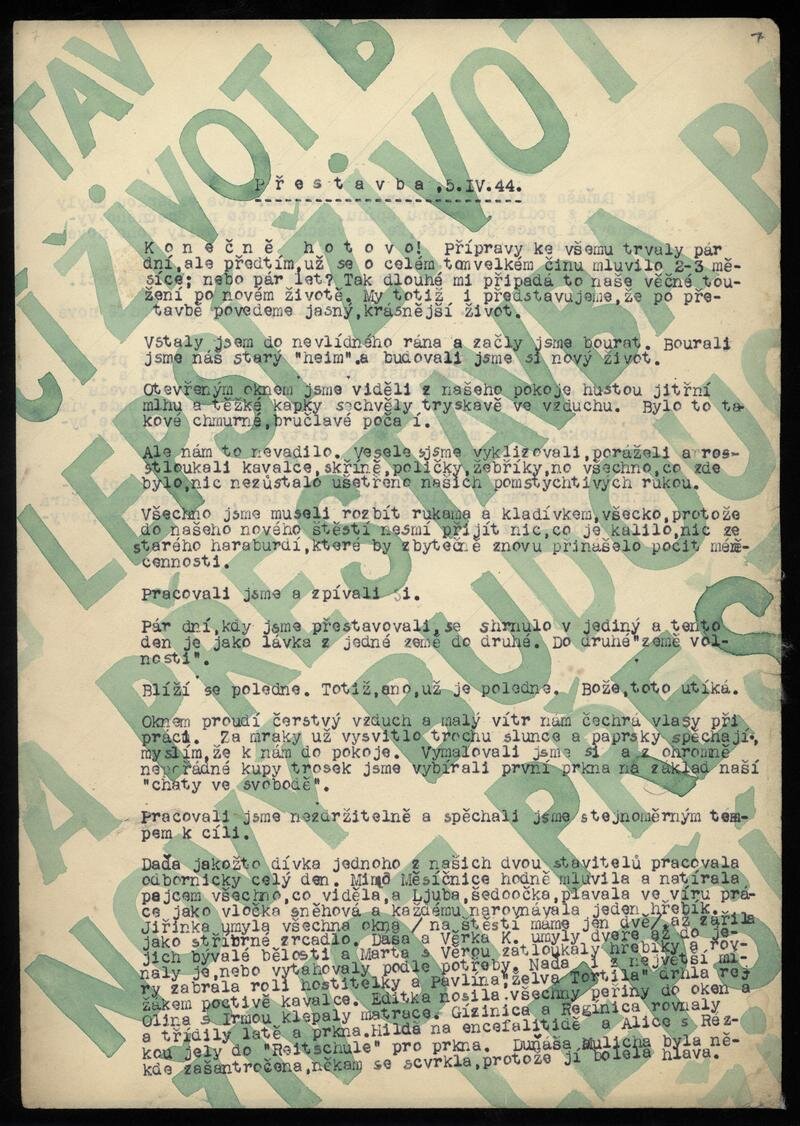

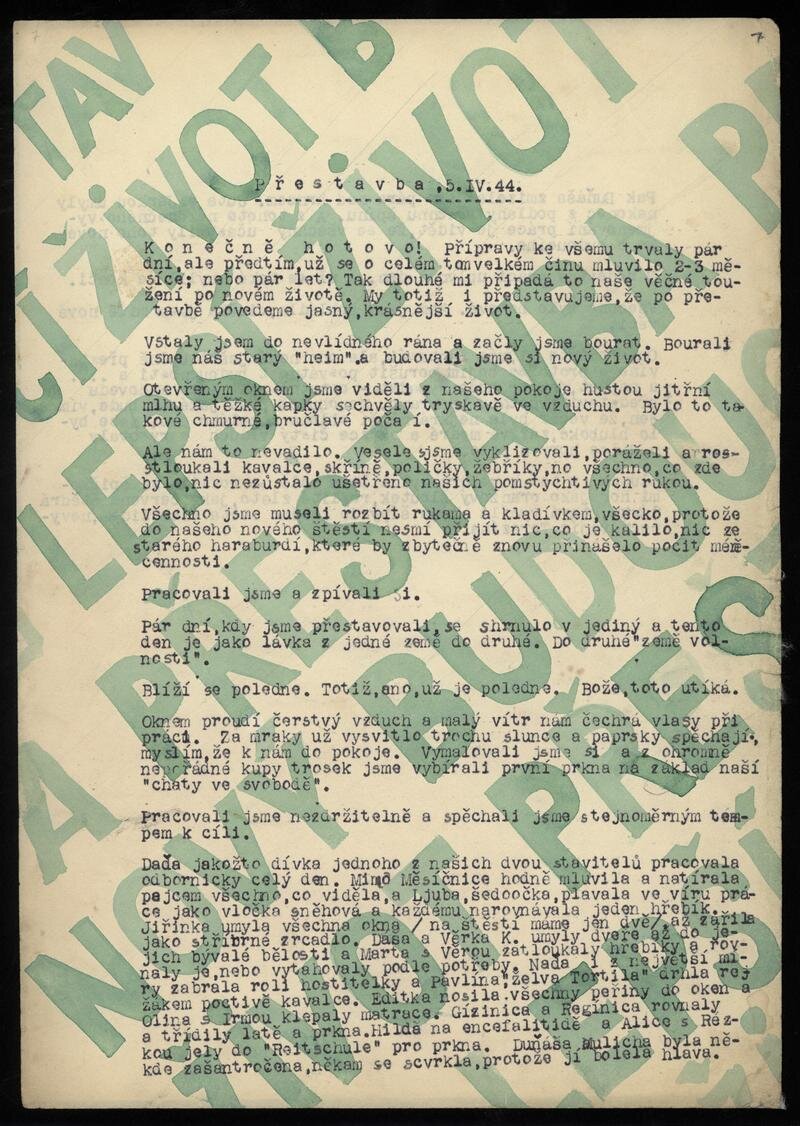

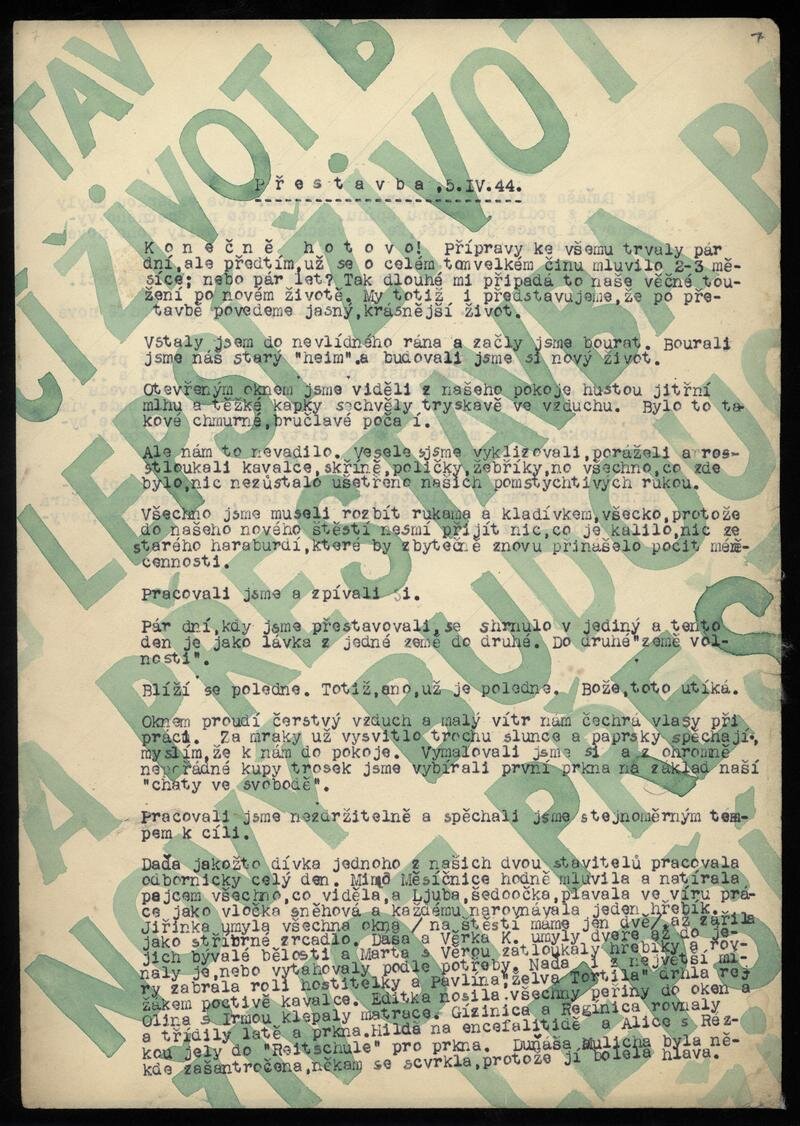

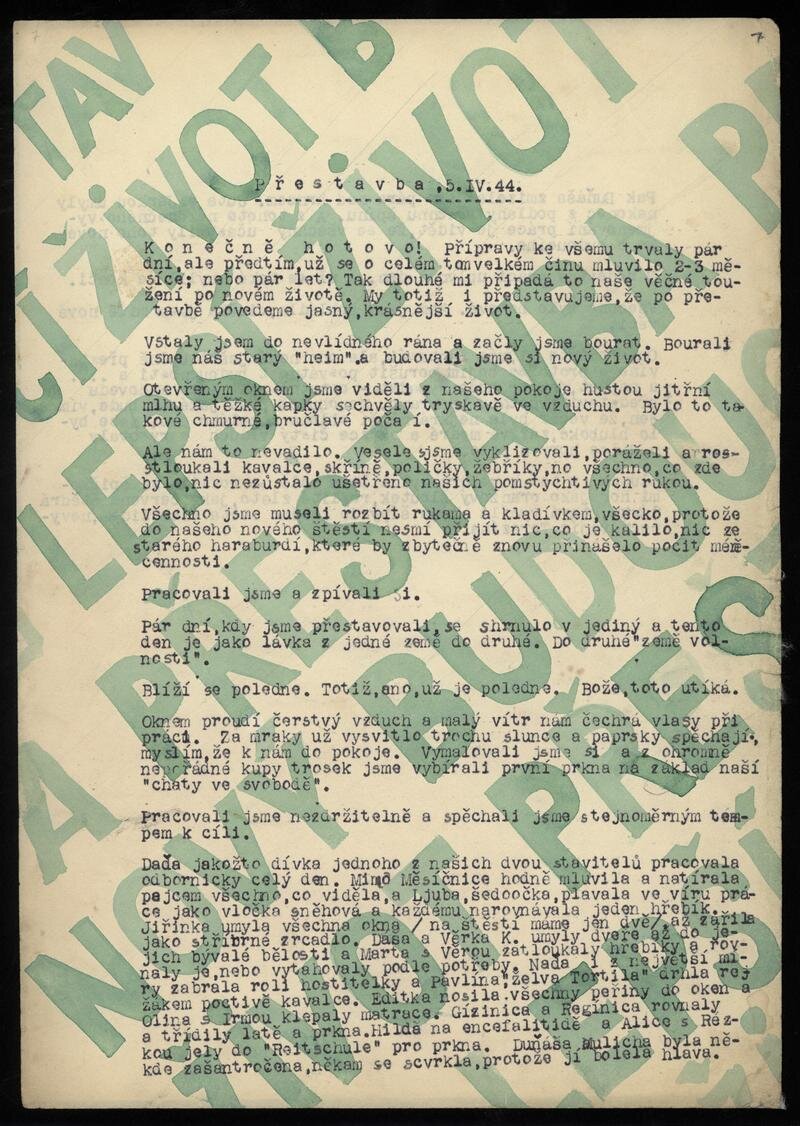

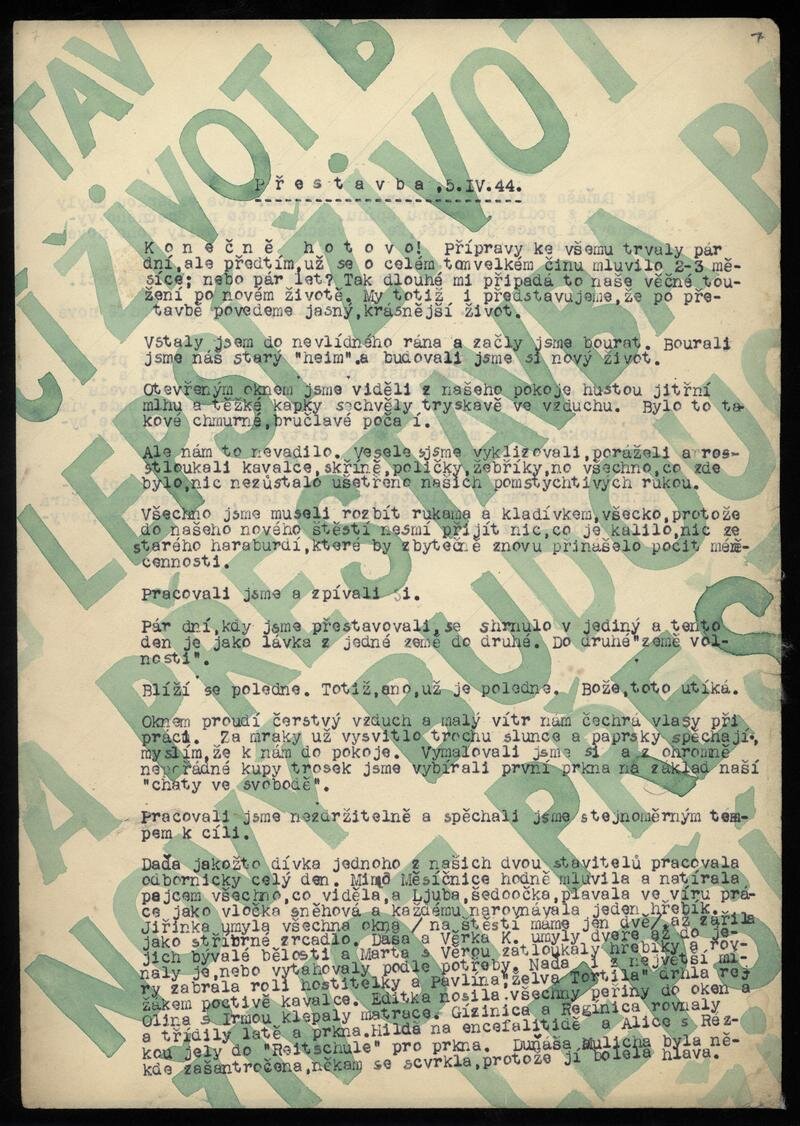

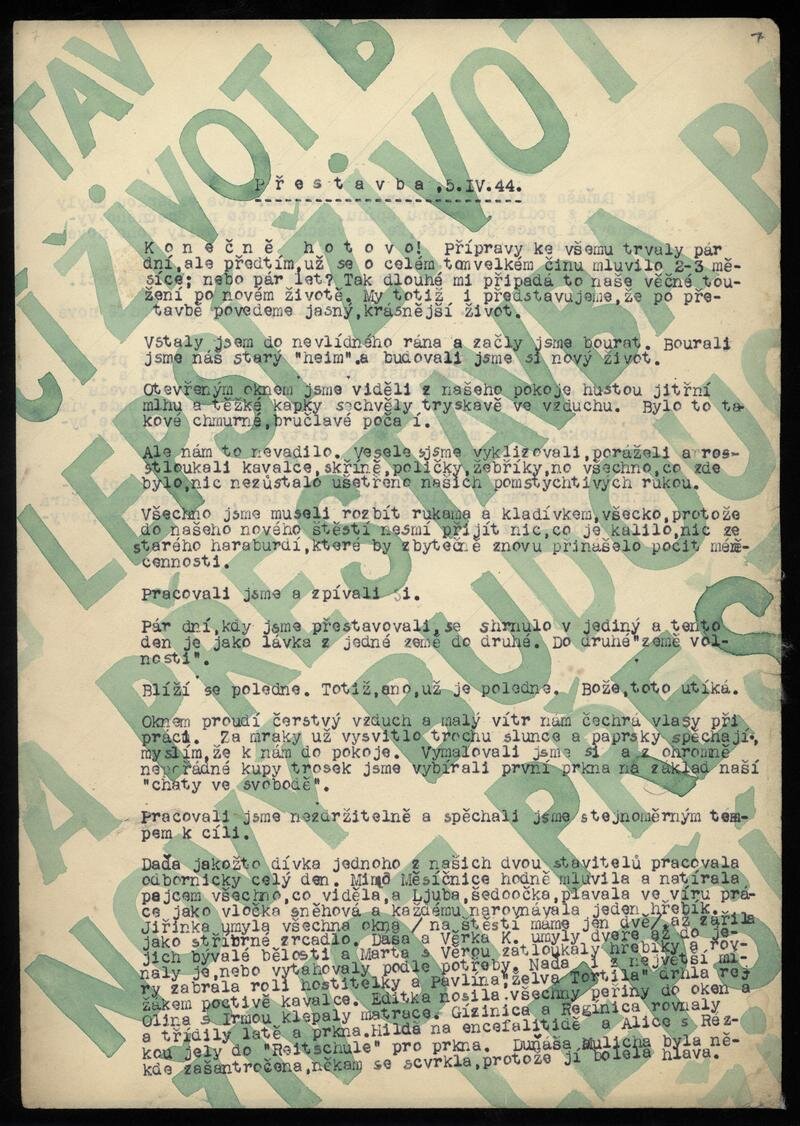

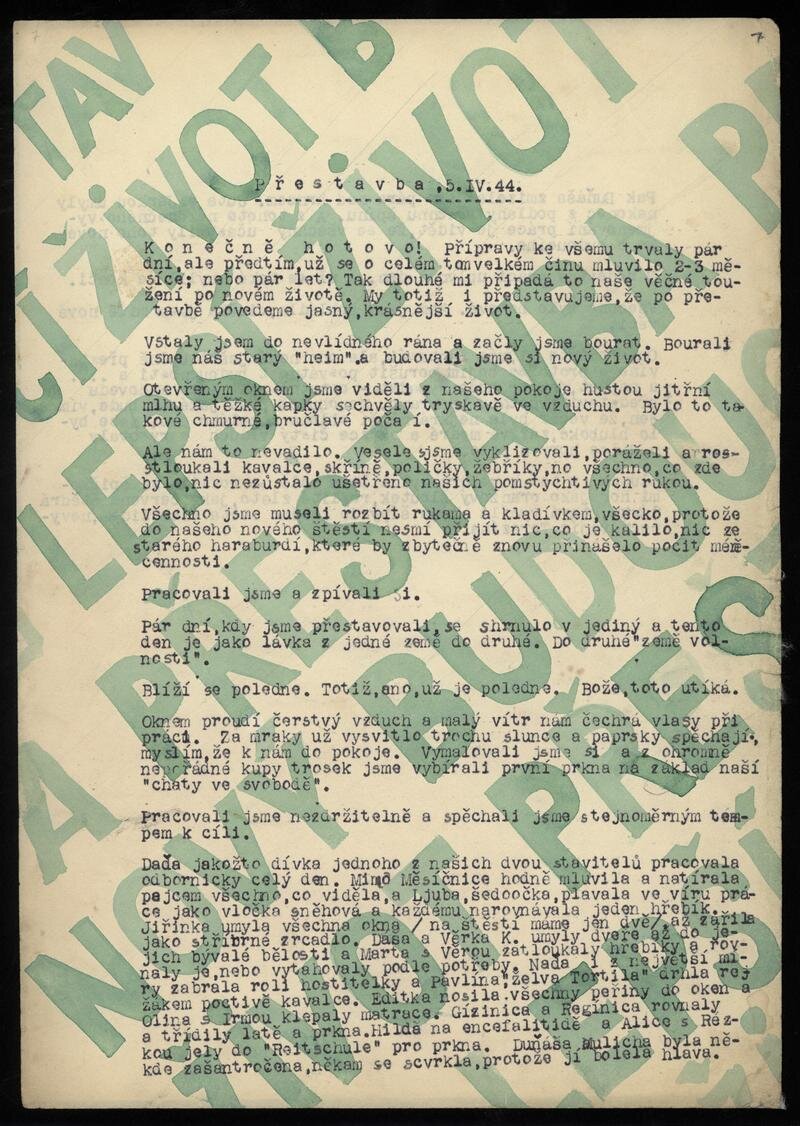

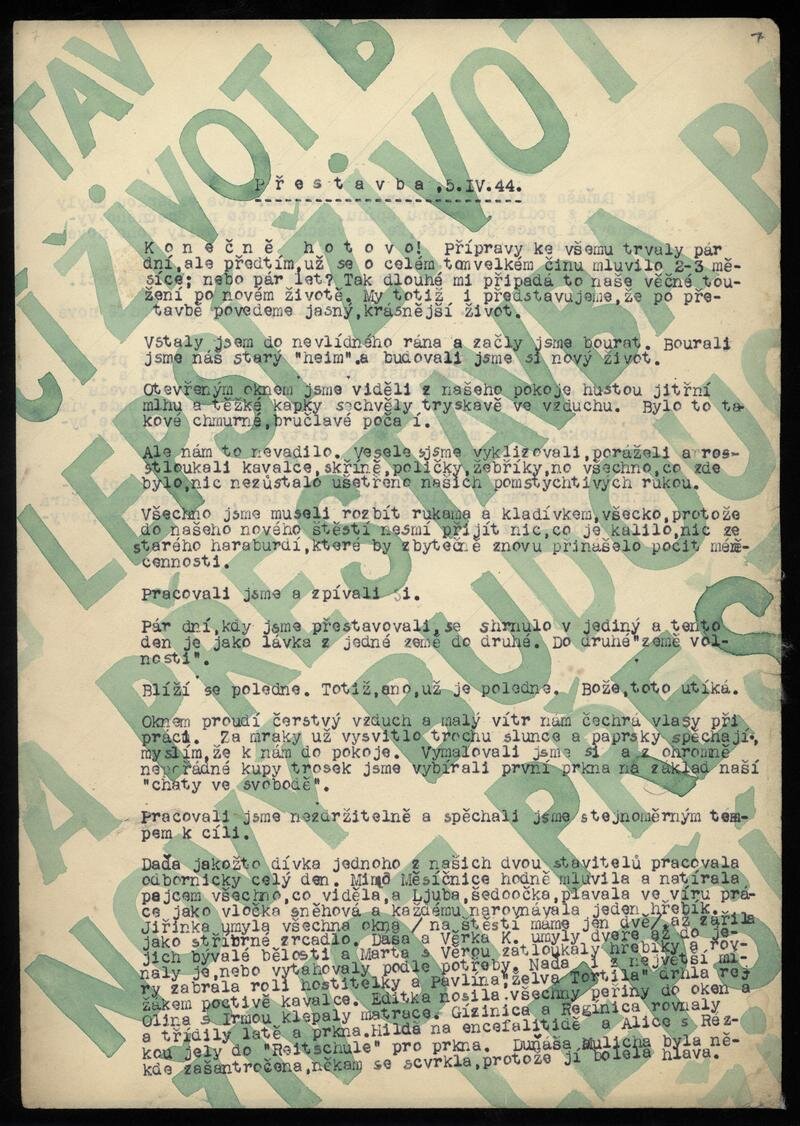

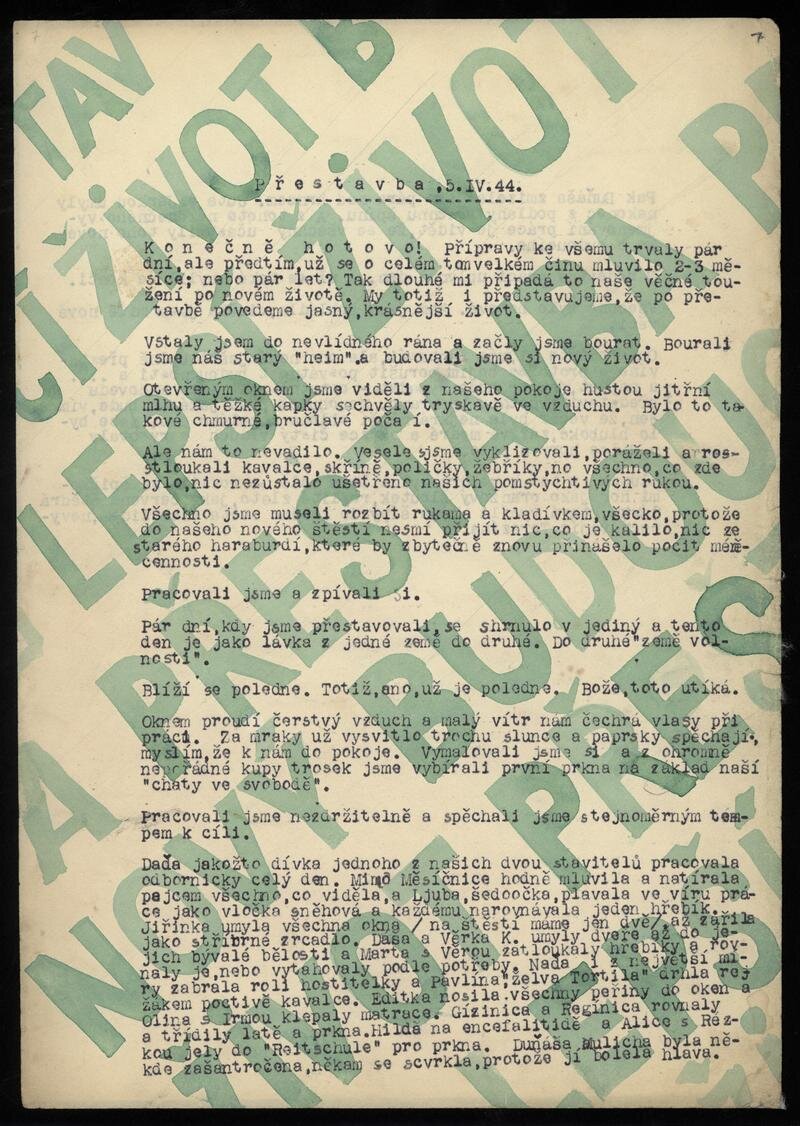

Kamarad is an underground handmade magazine – or zine – that was published by about two-dozen Jewish boy prisoners of the Terezin Ghetto from October 1943 to September 1944. Kamarad means “friend” in Czech.

WHY WAS KAMARAD CREATED?

“Today we are launching a magazine that is supposed to be a picture of our home. It is our first independent step forward. It should not only be fun and entertaining during times of boredom, but it should also represent its writers. Let’s make it as good as possible and hope everyone who contributes will be a real kamarad (“friend”) to us in the future.”

Kamarad was created as a way for its boy-prisoner contributors to establish both some semblance of normalcy and an alternate reality – in the form of a magazine production – to help offset the trauma and chaos of imprisonment and ghetto life. The magazine was viewed as a “friend” in a true sense of the word – a place to vent and learn, and a source of self-esteem.

WHO WROTE FOR kamarad?

"I can say that Kamarad has been working perfectly so far, except for the only Friday when it didn't come out, at a very turbulent time. The cooperation of all of us was created and perfected for two-and-a-half months to entertain and teach us. It became something so close to us and joined us so perfectly that it feels just as obvious to us as, as other old customs in our homeland.”

More than two-dozen boys aged 11 to 15 years old produced 22 issues of Kamarad. By Kamarad’s seventh issue, the boys had divided themselves into the following groups: “plutocrats,” “democrats,” “bourgeoisies,” “shallots” and “proletarians.”

-

Ivan “Ivča” Polák

-

Tomáš Gans

-

George Gans

-

Jiří Schulhof

-

Jiří "Koko” Schulhof

-

Michal “Miškus” Kraus

-

Pavel “Mydlajs” Gross

-

Oskar “Sunshine” Pick

-

Petr “Bejk” Beck

-

Herbert “Supajda” Grotte

-

Josef “Pepek” Běhavý

-

Jan Koretz

-

Otto “Hastroš” Wasserman

-

Harry “Mozeles” Ozers

-

Pavel “Feldmouš” Feldmann

-

Petr “Petulák” Freund

-

Jiří “Pensista” Gans

-

Jiří “Čingaškuk” Gross

-

Jiří “Honítko” Hahn

-

Fredy “Fredynka” Klein

-

Honza “Hanuš” Koretz

-

Petr Pavel Lekner

-

Petr “Spáč” Löwy

-

Pavel “Kamčus” Mautner

-

Pavel “Šiml” Schimerl

-

Marcel “Schwarzel” Schwarz

-

Michael “Strejda” Strenitz

-

Petr “Pejdy” Wiener

WHERE WAS KAMARAD PUBLISHED?

“Suddenly, we see a horse-drawn carriage driving, and behind the car, a whole procession of old men, old women and children. We immediately knew what that meant. The car was loaded with potatoes and people behind the car tried to get them out. ‘Poor people,’ I thought, ‘when raw potatoes have to be eaten from hunger.’”

– Jiří Schulhof

Terezin’s Building Q609 was a one-story house with more than 10 rooms that housed boys and girls from Czechoslovakia, Germany and Denmark. Room #A was on the first floor, and divided into three sections to separate the boys of different ages. The building included notable residents such as writer/playwright Norbert Frýd and Karel Bermann, who would survive the Holocaust and sing in the opera at Prague’s National Theater. Although they weren’t directly in charge of the children, they devoted time to singing with them or acting with them in informal plays.

“It is about five minutes before 7. In the room, you can hear a satisfied rest. That silence is broken by his hoarse voice, the biggest enemy of Room #A: the alarm clock. Then comes the grumpy, sleepy voice of a slumberer, who swears at an unpleasant awakening. A boy who cares a lot about getting up gets up. From the corner where Hahn lives, a sleepy voice growls: ‘He who rises is an ox!’”

Still, Room #A’s boys were subject to a strict regimen. Morning meant cleaning up and going to work. Noon meant a supervised lunch, and five o’clock meant dinner time. Eight o’clock meant that the boys had to be in bed, where counsellor Jiří Fränkl would read to them for an hour. Fun, informal activities like soccer, table tennis, theater, horseplay, handicrafts and after-hours “detective stories” were offset by events illustrating the Ghetto’s harsh realities, such as mass typhoid vaccinations.

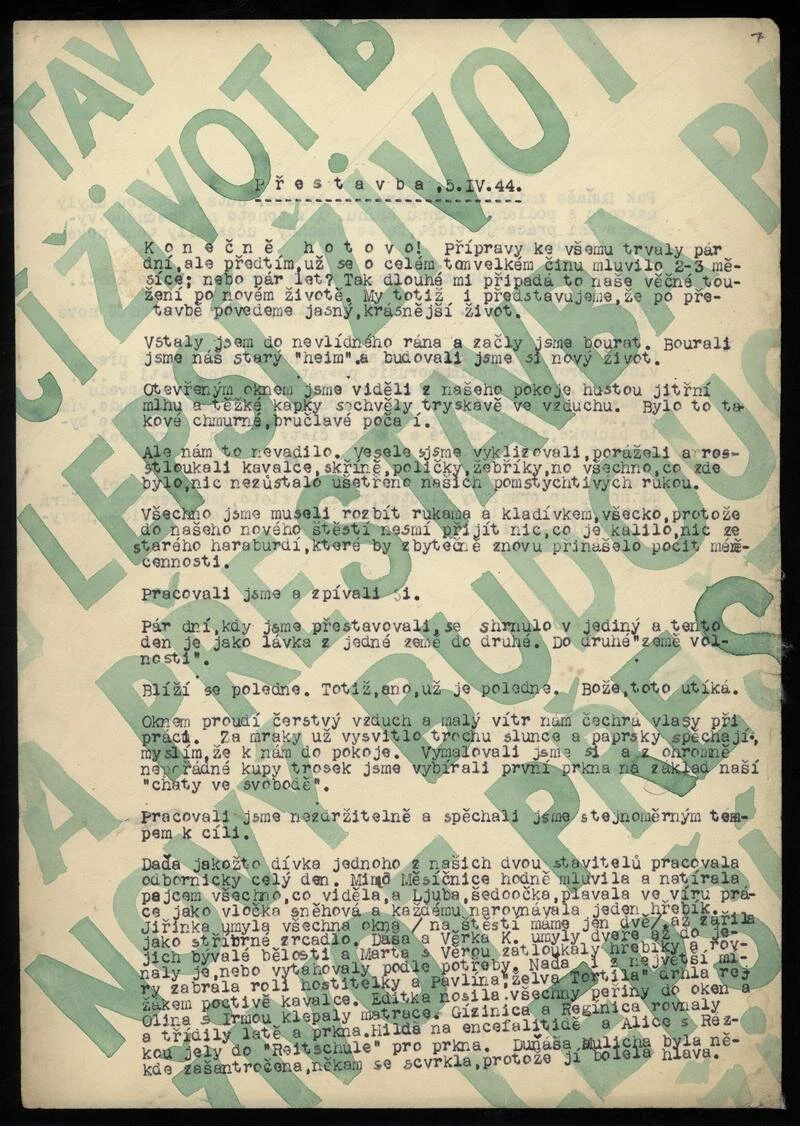

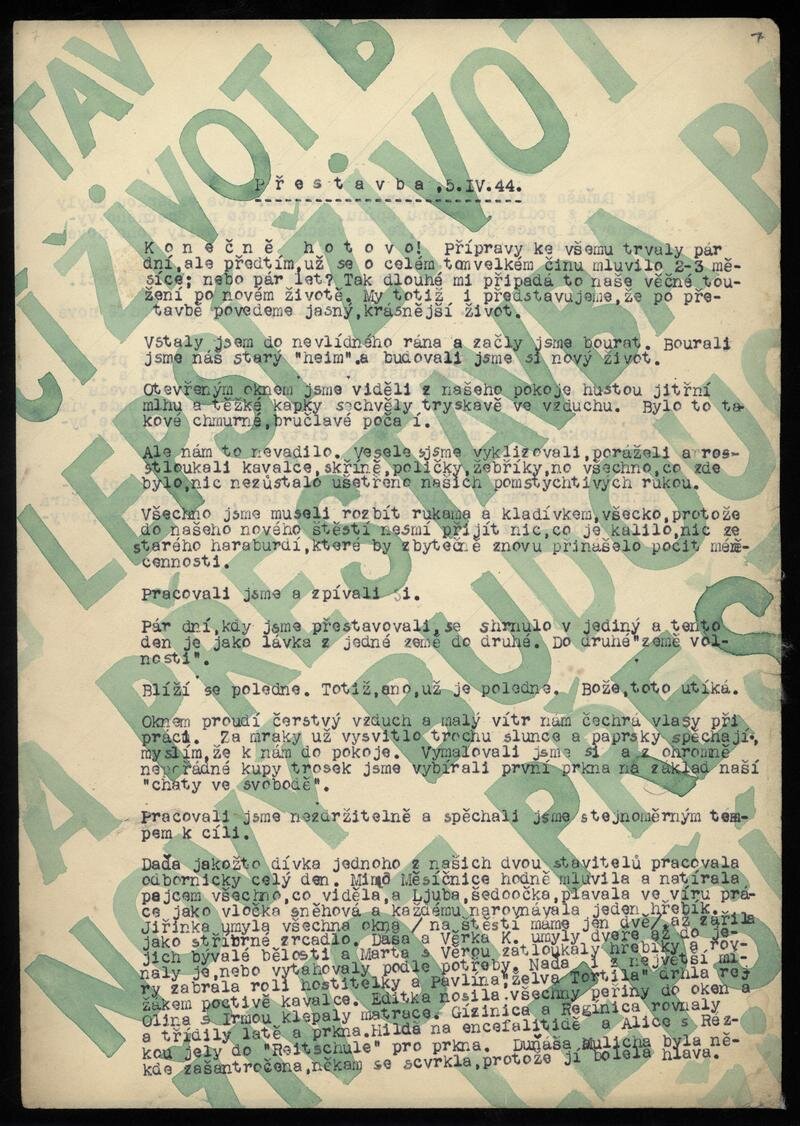

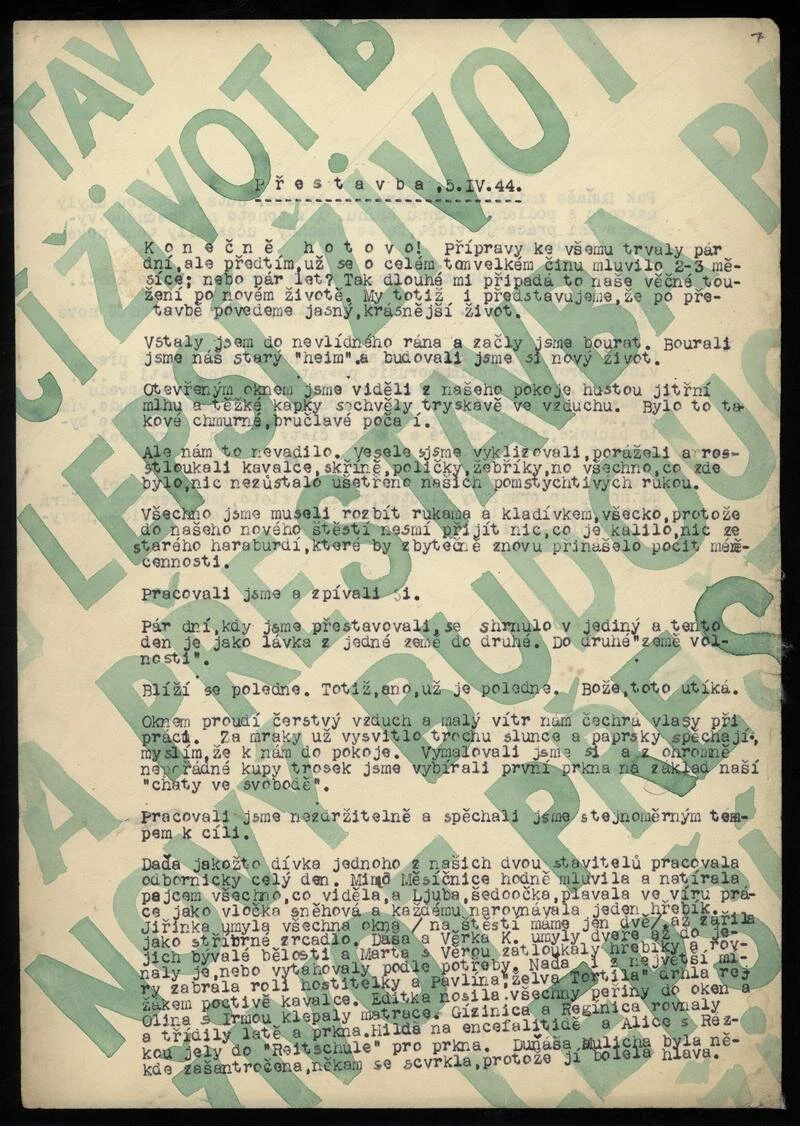

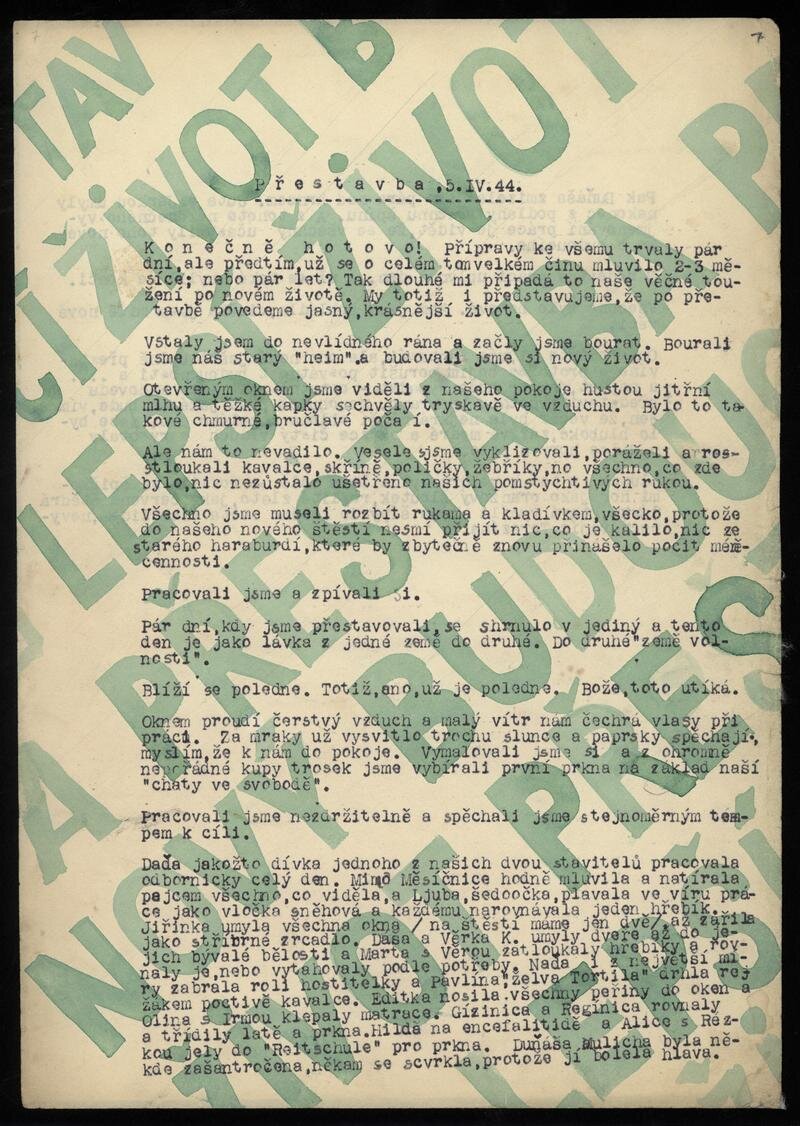

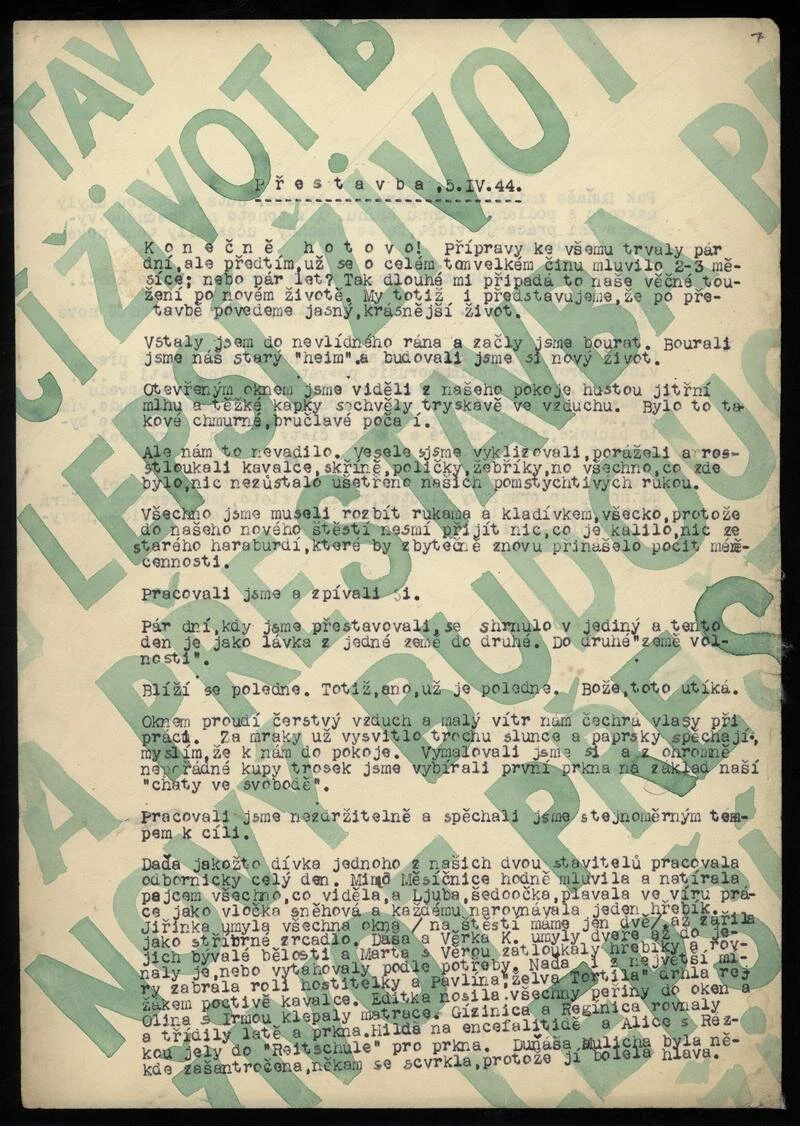

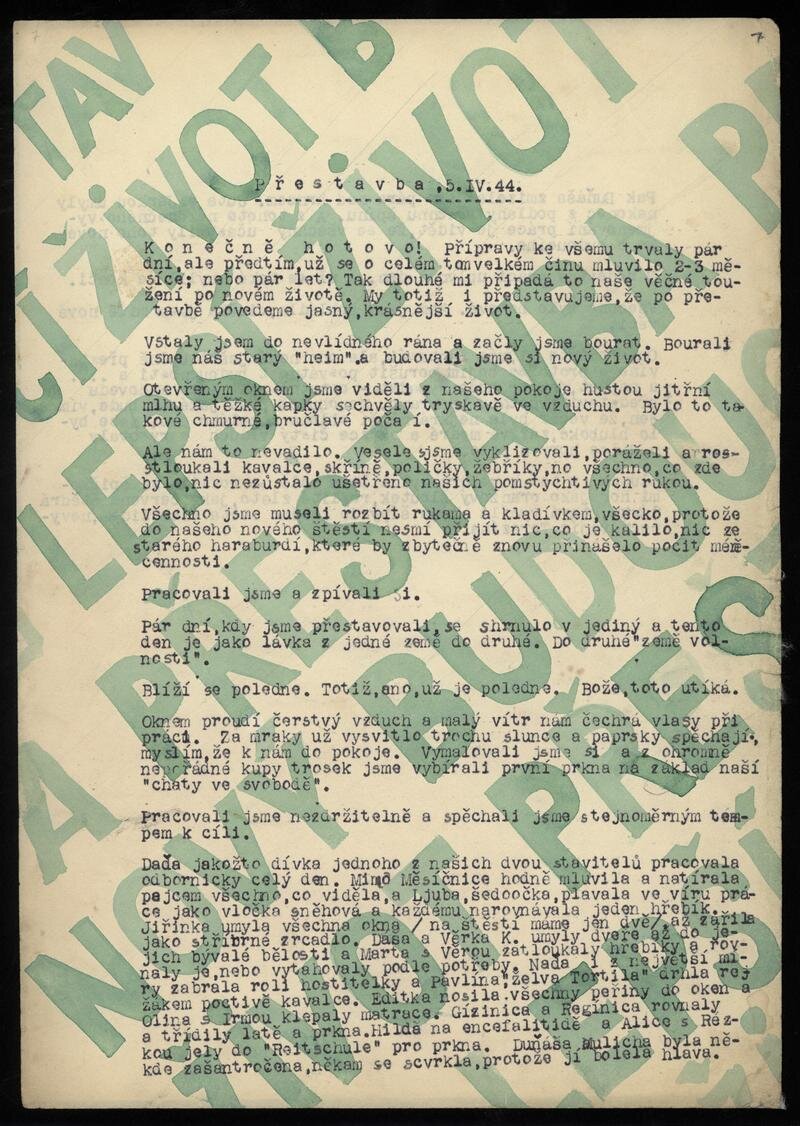

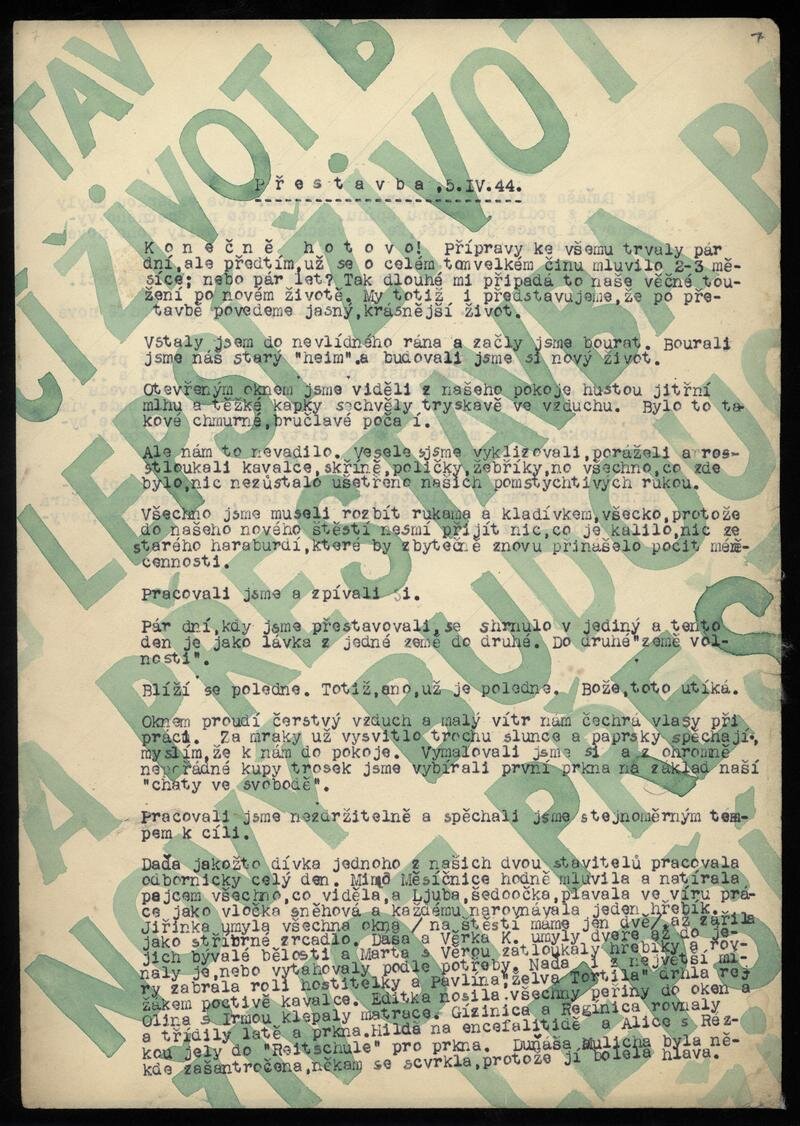

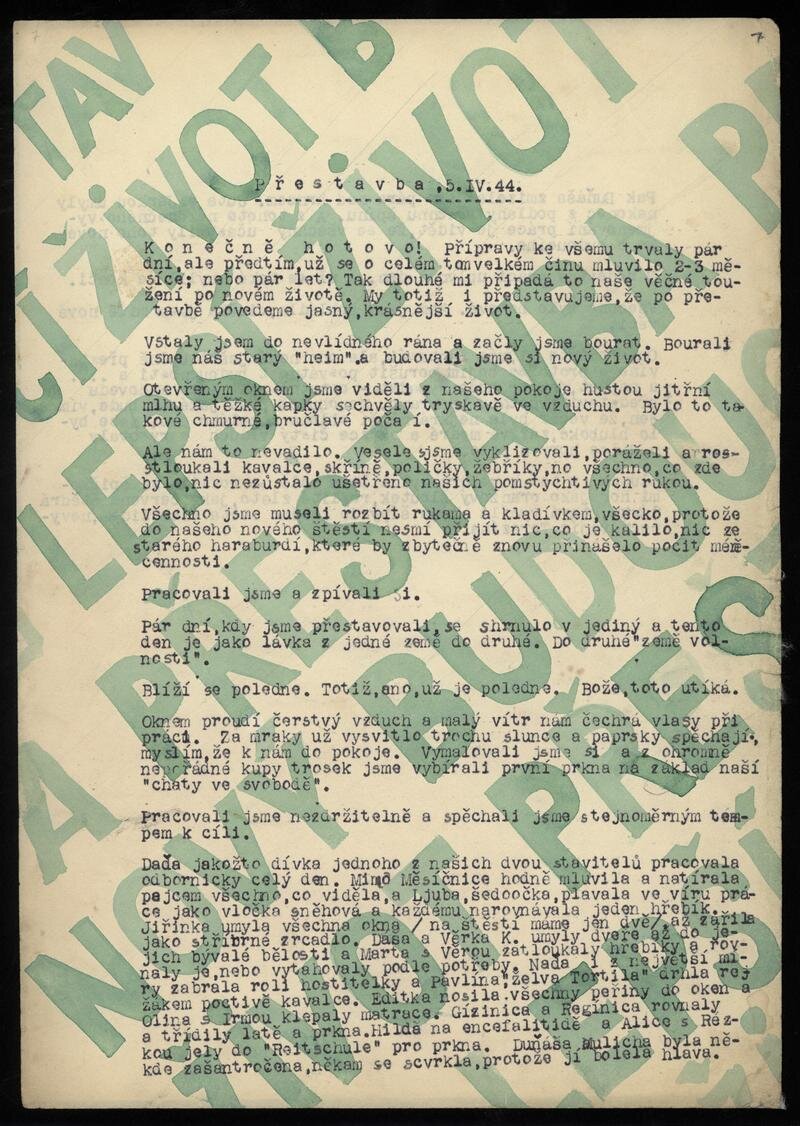

Editor Ivan Polák still found the time to transcribe and rewrite submitted articles, and would then handwrite the magazine on his bunk using two sheets of paper, ink, pen, pencil, eraser and watercolor. On Friday, Polák would bring the unfinished magazine to his mother, who would sew together the magazine in blue and white ribbon. On Friday nights, Polák would ceremoniously present the new magazine to the rest of the boys.

WHAT DID KAMARAD’S CREATORS WRITE ABOUT?

“These days have derailed us from normal life, but now that everything is over, we must work with double the force.”

– Ivan Polák, Kamarad Editor-in-Chief

Many of Kamarad’s early editions included so-called “novels,” which were series of short fiction stories that spanned across multiple issues and expressed the boys’ wish for freedom. One novel was about a trio of Jewish boys who’d been banned from attending school and instead conquered much of northeastern Canada. Contributor Josef Běhavý told the tale of a rocket-obsessed university student who befriends a boy whose father’s company makes and stores explosives, and the two collude to make a rocket. Contributor Jan Koretz wrote about a heroic ship captain who rescues the kidnapped child of Icelandic royalty.

With so many boys who’d never previously met being imprisoned and forced to live together in a single room, Kamarad’s articles often focused on resolving the inevitable conflicts. The boys had to balance out the willingness to write about the Ghetto’s tragedies – the dying elderly, the hungry, the tight quarters and resulting diseases – with concerns over being caught and punished by the Nazis for publishing a magazine. The nuances of Ghetto life were also explored: for instance, theft was perceived as a vice, unless something was stolen in order to facilitate life, in which case theft could be heroic. One writer whose identity wasn’t confirmed touched upon the wrenching experience of watching friends being deported to “the East,” which was shorthand for death camps such as Auschwitz.

“We went to help our friends with luggage – especially to weak Steinýrs, whose parents are not healthy. We all go to the station. Here and there, stretchers with the sick flicker. A few soothing and encouraging words, the last greeting and they are already in the car. We stand for a while and watch.”